When William Soliman was a young sales rep at Merck & Co. in the early 2000s, he ran into a supervisor during a training who asked him to do something with data he thought was shady. The data in question was for Vioxx.

“He said, can you please tell those three MSLs (medical science liaisons) that keep poking holes in the data and keep talking about the concerns with the data to stop, because it's discouraging and worrying the other MSLs?”

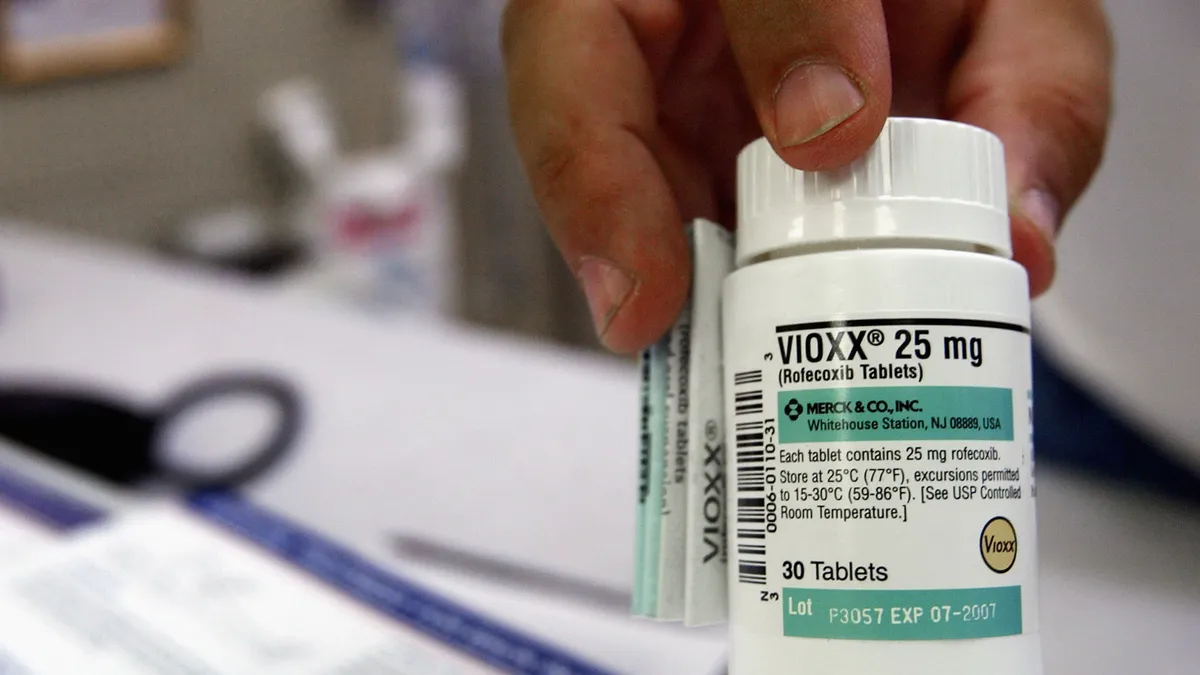

Merck allegedly knew that its blockbuster arthritis drug increased patients’ heart attack and stroke risk, yet concealed that data and misled the medical community and the public for years. In 2004, Merck withdrew Vioxx from the market, but not before it potentially caused between 88,000 and 140,000 heart attacks in the U.S., according to a study in The Lancet. Of those, tens of thousands died.

In 2007, Merck agreed to pay $4.85 billion to settle cardiovascular claims after 60,000 plaintiffs sued the company.

“I was probably 26 years old,” Soliman remembers of the incident. “I was nervous because it’s your boss … I was worried I was going to lose my job if I pushed back.”

Although he agreed in the moment to do what his boss asked of him, he never did.

“But I felt like I was put in a difficult position,” he said. “That experience definitely (left) an indelible mark for me.”

Now, as the founder and CEO of the Accreditation Council for Medical Affairs (ACMA), Soliman is working to prevent these kinds of conflicts between medical affairs departments and marketing.

Today, ACMA certifies and accredits medical affairs and medical science liaisons for pharma and biotech companies, and according to the organization, has certified more than 5,000 pharma industry professionals from more than 200 companies.

“We're the only accredited program for medical affairs and MSLs in the world,” he said. “We're accredited by IACET, the International Accreditors for Continuing Education and Training.”

In particular, Soliman is focusing his efforts on overcoming a lack of competency standards in the profession to help avoid more pharma scandals down the road.

A need for standard competencies

Soliman founded ACMA after spending years working in medical affairs for companies like Eisai, Gilead Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim and AbbVie.

“What I found in working with many companies is that there was no uniform standard within the area of medical affairs,” he said. “Medical affairs, generally speaking, is a relatively newer function in the overall history of the pharmaceutical industry, and really until (the ACMA) came on the scene, there was no universally recognized competency standards in that space.”

"Obviously every company is going to be different, but the core competencies of the medical affairs professionals should be relatively the same."

William Soliman

CEO, founder, ACMA

Medical affairs professionals within pharma and biotech companies help communicate scientific and clinical information to the medical community. Yet there aren’t standardized “requirements” for holding such an important position.

Soliman likens the relationship to hairdressers and clients.

“In the United States, to cut hair, you have to have a license,” Soliman said, yet there was no such basic threshold for medical affairs professionals.

“You could be an MSL, and no one would really vet how much you really knew,” he said. “Obviously every company is going to be different, but the core competencies of the medical affairs professionals should be relatively the same.”

Using data and feedback from pharma companies, the ACMA developed key performance indicators and metrics around what makes an effective medical affairs professional and used that data to develop a curriculum that teaches core competencies. These indicators include clinical trial design, interpreting biostatistics and understanding health economic outcomes; regulatory and compliance issues like the Sunshine Act and anti-kickback statutes; along with professional proficiencies and ethics. It also offers certificate programs such as the Regulatory Affairs Expert Program and Clinical Development Expert Program, and in 2019, launched the Prior Authorization Certified Specialist program and established the National Board of Prior Authorization Specialists.

Ethics and medical affairs

A lot has changed over the years for medical affairs professionals and departments.

“Back in the day, MSLs and medical affairs, (weren’t) reporting to a medical head. You still worked in marketing,” Soliman said. “You can’t have a reporting mechanism where you’re reporting into a commercial head. A commercial head should never be influencing medical affairs activities.”

Today, that’s what Soliman calls a “no-no.” Medical affairs folks should not act as “glorified salespeople.”

Growing up in Jersey City, New Jersey, Soliman said he developed his ethical core by watching his parents. His mother came to the U.S. from Syria and Jordan, and his father emigrated from Egypt with so little money that he actually lived at the JFK airport for three or four days when he first arrived.

“He didn't know where to go,” Soliman said.

Eventually, Soliman’s father found his professional path, and owned businesses and real estate throughout the area. As a kid, Soliman often accompanied his father to work and remembers a man who used to come into one of his stores and give him a dollar every time he visited. This man also offered Soliman’s father $10,000 a week to work for him.

“That's a lot of money in 1986,” Soliman said. Yet his father turned it down because of the man’s ties to organized crime.

“He is the kind of guy that always acted with the highest integrity,” Soliman said of his father.

Despite his parents finding business success later in life, Soliman said he grew up poor. But his parents encouraged his interest and abilities in science and math. He went on to earn his undergraduate degree in biochemistry from NYU and a master’s and Ph.D. from Columbia, and eventually built a long pharma career.

Even today, Soliman’s early pharma experiences stick with him, and he believes the industry can learn from its controversies. He points to the opioid crisis, which was fueled by the way Purdue Pharma misled healthcare providers and consumers about the addictiveness of OxyContin, as well as the many deaths, lawsuits and settlements that stemmed from those actions, as a clear window into how pharma can improve the way it operates. And he believes that having well-trained and ethical medical affairs departments is key to building trust and integrity with healthcare professionals and the public, as well as keeping patients safe.

“Let's not wait for the next opioid crisis … let's be ahead of the game,” he said. “The opioid crisis is really the tip of the iceberg in terms of being vigilant and proactive in our standards, and our procedures, and our ability to hold each other accountable.”