The mystery is over. After a year of speculation, the Biden administration unveiled the first 10 drugs subject to Medicare price negotiation yesterday, kickstarting a new year of back-and-forth between manufacturers and the agency. And now the real question is, just how much will pharma R&D be impacted?

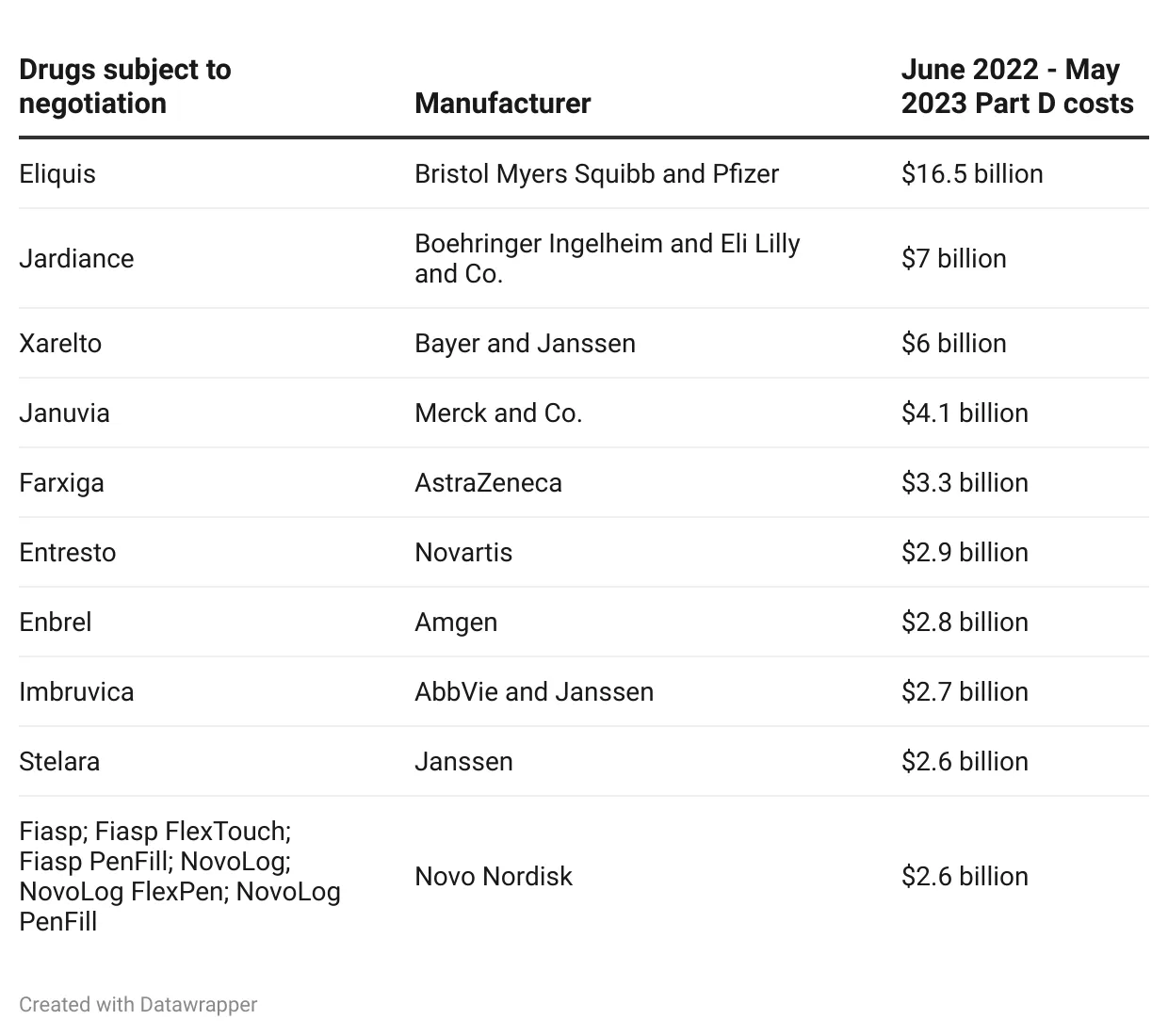

There are few surprises on the initial list, which comprises mostly cardiovascular, diabetes and cancer blockbusters, including the blood thinners Eliquis and Xarelto, Type 2 diabetes medications Januvia, Jardiance and Farxiga and the blood cancer therapy Imbruvica.

Many analysts had predicted those drugs and others would appear among the selections after the CMS announced last year that it was choosing among the top 50 drugs it spent the most on under Medicare Part D that didn’t have generic competition.

However, John Stanford, executive director of Incubate Coalition, a venture capital advocacy organization, said that for many in the industry, seeing the official list heightened the reality of drug pricing.

“We're going from 0% of people caring about it to 99% [to]100% of people saying: ‘This is a totally new landscape,’” Stanford said.

While speculation around the impacts of Medicare negotiation have run rampant since the CMS was granted the authority under the Inflation Reduction Act last year, the list provides the first actual view of how the agency is approaching the process, Stanford said. And so far, it has confirmed many of the industry’s fears.

Disincentivized development

In particular, Kirsten Axelsen, a consultant for the Partnership to Fight Chronic disease and visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said the CMS makes clear that Medicare price controls will apply to all FDA-approved indications of a drug, rather than just the initial indication.

For instance, Jardiance is noted for both heart failure and diabetes on the list and Farxiga is recorded as a diabetes, heart failure and chronic kidney disease treatment. Based on those observations, Axelsen said the industry can expect the agency to “group together as many drugs of the same moiety as possible,” on future drug pricing lists.

Pharma executives and industry groups had previously urged the agency against the approach, arguing that lumping multiple indications for a drug into negotiations would disincentivize companies from researching a molecule for more than one disease, thereby increasing research costs.

David Ricks, CEO of Eli Lilly and Co. even suggested that he would alter the company’s development strategy to pursue multiple molecules with staggered timelines to “spread their bets” and keep the business attractive for investors if the CMS took such an approach.

“It's doing exactly what many of us are concerned about, which is creating a disincentive to add second or third indications for the same drug,” Axelsen said of the list, noting that she expects more companies to begin rethinking their strategies. “The message to manufacturers is not to develop for a second or third indication.”

Because the list so heavily targets drugs for widespread chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease, it also draws into question drugmakers’ strategies for those indications, Axelsen said.

Drug manufacturers may now think twice about developing would-be blockbuster medications in disease areas affecting large portions of Medicare patients, because the new therapies could initially struggle to compete with negotiated prices, or eventually, be added to the list, she said.

"When the prices come out, that's when we're going to know just how much of a gut punch this is to the industry and how much it could impact biotech investment."

John Stanford

Executive director, Incubate Coalition

Areas of drug development that may be less impacted include treatments for diseases that impact patients younger than 65, and therapeutic areas where the barriers to launch are lower, and where companies can reap profits more quickly.

Rethinking rebates

Analysts have also questioned whether the government-negotiated prices for drugs on this first list will be lower than the rebate prices currently offered to Medicare Part D plans.

Many of the drugs the CMS chose are already “deeply discounted,” Axelsen said. She suggested that those prices will soon become the ceiling for how much companies can charge.

“If you're already discounting 60% or 70%, that's where CMS is going to start,” she said.

As the agency prepares to add 10 more drugs to its negotiation list each year, and then 20 per year after 2029, manufacturers with likely candidates for negotiation should rethink their rebate strategy, Axelsen said.

“If I were a manufacturer with a blockbuster drug, I would, especially toward the end of the life cycle, start thinking about pulling back on the discounts because they're going to become punitive,” Axelsen said.

Awaiting more clues on market impact

The announcement of the first 10 drugs marks only the beginning of what is sure to be a long negotiation process between drugmakers and the Biden administration. Companies with products on the list, including Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen and other pharma giants have until October to decide whether they plan to participate in the negotiations.

Most of them will certainly engage in negotiations, as they would otherwise need to withdraw their drugs from Medicare and Medicaid coverage or face an excise tax of up to 95% of their U.S. sales if they bowed out of the process.

Analysts and investors will be watching the negotiation process closely over the next year for more signs of how it could impact market dynamics. The next big insights are likely to come in September 2024 when the CMS publishes the maximum prices negotiated for the drugs, Stanford said.

“When the prices come out, that's when we're going to know just how much of a gut punch this is to the industry,” and how much it could impact biotech investment,” he predicted.

If the agency ignores the costs of R&D and manufacturing associated with drug development while determining prices, “then that's the signal that the entire marketplace is going to cool significantly” because of negotiations, he said.

However, if the agency makes minimal price cuts and signals that “they’re being fair arbiters,” he said investments may still slow, but won’t grind to a screeching halt.

“When we see just how draconian the price controls are, we'll decide just how much of the spigot we close as investors,” Stanford said. “The more draconian the cuts, the more chilling the impact on investment.”