Revolutionary drugs often get the bulk of attention surrounding medical advances. But their success in the real world is intrinsically tied to the screening process that finds which patients would benefit.

For biomarker assay maker Quanterix and their Big Pharma partner Eli Lilly, this interconnected relationship could develop personalized therapies for one of the trickiest neurological conditions out there: Alzheimer's disease.

Quanterix's technology platform, called Simoa, allows the detection of biomarkers at ultra-small concentrations. For it to work well, the platform needs antibodies that tell the sensitive technology what to look for, Quanterix CEO, Masoud Toloue, says.

"We're identifying detection capabilities so that we can detect biomarkers at femtomolar levels," Toloue says. Femtomolar refers to a very, very small concentration of molecules in a sample. "The next thing you need is important biomarkers."

That's where Lilly comes in. The partnership between Quanterix and Lilly is symbolic of the interdependence between pharma companies developing new drugs and the diagnostic companies that can identify the patients who will benefit from treatment.

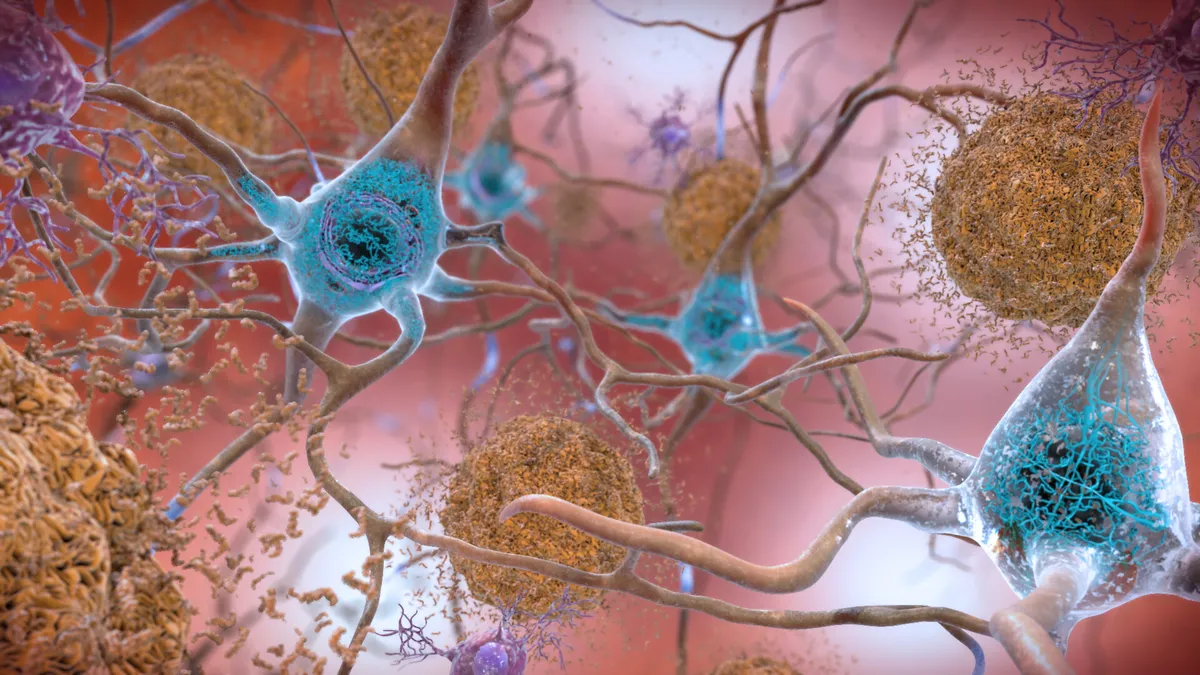

Lilly's P-tau217 is a biomarker the company believes can determine Alzheimer's disease pathology through plasma. Their drug donanemab, which targets beta amyloid plaques in the brain thought to contribute to Alzheimer's symptoms, also led to 24% lowering of the tau biomarker in phase 2 study results released last year.

"The agreement and partnership with Lilly is around access to Lilly's 217 antibody technology," Toloue says. "This is an important next step for our company, and working with a great biomarker and the technology combined, we think is going to make a big impact."

Lilly Chief Medical Officer, Dan Skovronsky, said on the company's first-quarter earnings call in April that the use of biomarkers to select patients, particularly in clinical trials, allows them to drill down into how the drug can perform most effectively in a crucial window.

"These aren't patients who have too much tau in the brain, because we think they're beyond the point where anti-amyloid drugs will help them — nor are they patients with no tau in the brain because we think those patients won't progress even on placebo and therefore won't get benefit from a drug," Skovronsky said. "So we think selecting those patients will give us the opportunity to see better efficacy on a more homogenous background."

The invention of the microscope

To understand the impact that ultra-sensitive biomarker assays can have in precision medicine, Toloue hearkens back a few centuries to another important invention: the microscope.

"A couple hundred years ago … you had the discovery of the microscope, and you could see microorganisms," Toloue says. "With Simoa, I view that as an analogous technology in that we can measure proteins at levels that were previously not available, or not able to be seen or detectable, and that's improving."

Being able to see deeper into what is ailing a patient can help improve outcomes, Toloue says.

"If you can detect these biomarkers efficiently and early, that helps with more efficacious therapies and allows a better health profile for someone in the future," Toloue says.

Simoa uses magnetic particles that are coupled with an antibody, and then the detection of a biomarker generates a fluorescent molecule that can be found even at low concentrations.

For Alzheimer's, a notoriously challenging realm of drug R&D, the biomarkers could determine not only which treatment is useful but which new therapies could work for certain patients.

"It's been a few decades where the whole Alzheimer's market has been trying to identify the right target and the right detection mode," Toloue says. "And very clearly, there haven't been a lot of successes until recently with a few new therapies that are coming to market."

Therapies like Biogen's Aduhelm, approved last year with much controversy surrounding effectiveness and trial design, have shown just how challenging the brain can be to treat.

"It's been a difficult stretch, and this whole neuro area hasn't been easy," Toloue says.

Hand in hand

"If you take the broad definition of precision medicine … to put together a therapy that's going to be unique for one person, I think in the area of neurology, that will happen at one point in the future," Toloue says. "The testing, the screening, the triage, and ultimately the diagnostics are going to have to go hand in hand with therapies."

And this type of precision medicine can help treat patients much earlier in their disease state — a truly important effort for Alzheimer's in particular.

"With a successful therapy in the market comes a need to do decentralized testing, and making testing available and accessible to everyone at far earlier stages," Toloue says. "And making it accessible and identifiable early is also going to help with the success of the therapy and the drug."

That work isn't done — Quanterix received funding from the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF) in March to develop what’s called a multi-analyte immunoassay, which would enable simultaneous measurement of many substances.

"If we want to in the future replace imaging, we think it's a multi-analyte test, and the ADDF work is really for funding a series of prospective clinical trials," Toloue says.

Ultimately, the goal is to take the guess-work out of the diagnostic process. This kind of advancement could go a long way in reducing medical costs, and preserving precious time for patients and their families.

"When you look at the costs of imaging, the cost of getting cerebral spinal fluid, that's all very expensive," Toloue says. "So if you can do it in a blood test and screen the population to identify who is the best fit for therapy, that's incredible for both the providers and the patients."