Statistics released this month from the American Cancer Society present a double-edged sword: Deaths have declined steadily for three decades due to better treatments, lifestyle choices and detection. But on the flipside, cancer incidence is on the rise.

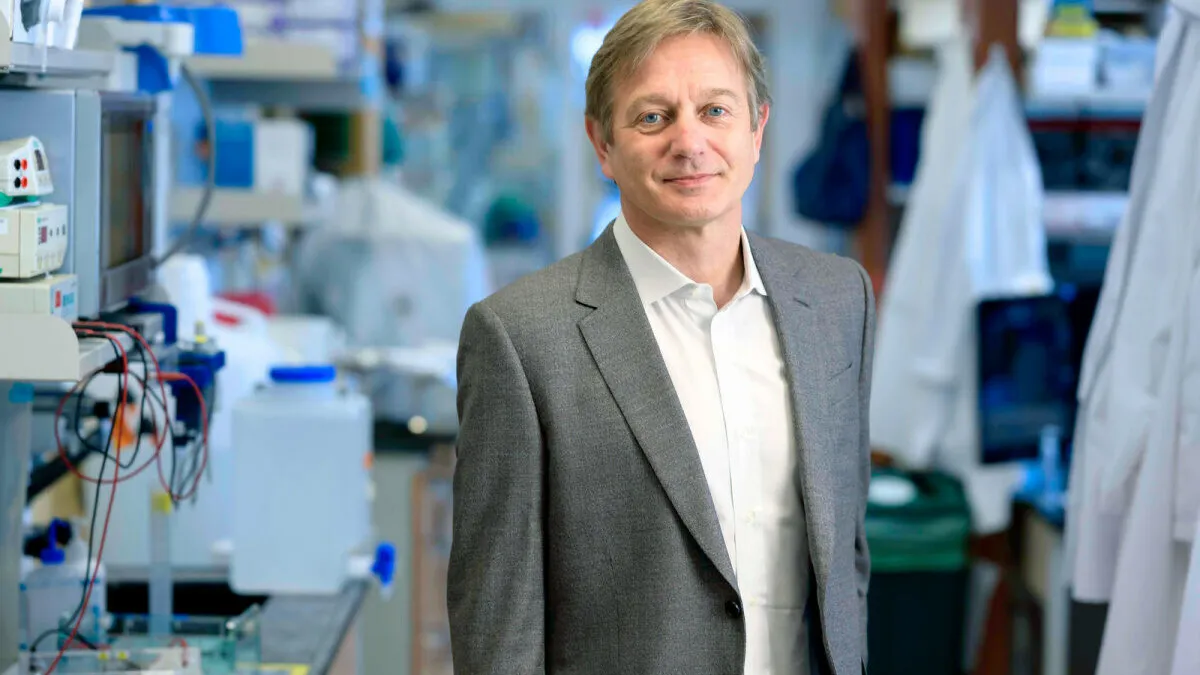

Dr. Marcel van den Brink, who served as an oncology leader for more than two decades at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York and last year joined the City of Hope Cancer Center — a nonprofit clinical research institution and hospital in Los Angeles — has seen the progress firsthand.

“When I did my training, the whole field of oncology was stale, a bad backwater — there was not much happening and we were just using chemo for so many patients, and that was it,” said van den Brink, who is the L.A. and medical center’s president, as well as chief physician executive. “At the time, getting cancer meant palliative care, and now we’re in a completely different world.”

One of the most impactful waves of innovation was the onset of immuno-oncology and the advent of checkpoint inhibitors that invigorate the immune system to fight cancer. Drugs like Merck & Co.’s Keytruda or Bristol Myers Squibb’s Opdivo and many more have helped many patients live longer lives. But, as indicated by the ACS figures, there’s still a great deal of work to be done to improve those treatments and find more effective ones to fight the many types of cancer predicted to affect a growing population of patients.

For that, van den Brink leans on one of his areas of expertise he says is often overlooked in oncology: the gut, and more specifically, how the millions of tiny organisms living within us change our immune system’s ability to fight disease and respond to treatment.

‘Diet as a drug’

The field of immuno-oncology can be improved with an understanding of the microbiome, van den Brink said.

“Checkpoint blockades were one of the breakthroughs of immunotherapy, and there are still more promising pathways in that same area,” van den Brink said. “But we also know T cells are not working in a vacuum against cancer — they are impacted from many, many sites, and that is a bridge to the microbiome.”

The human microbiome contains a tremendously diverse array of foreign microbes that contribute to the body’s equilibrium. If that balance tips in any direction, the outcome is highly unpredictable. But one of the possibilities that can arise from a microbiome that’s out of whack is an inability to fight cancer, van den Brink said.

“The microbiome is another organ that needs to be taken seriously — it’s the last organ we have discovered, and you need to understand what the function of that organ is to assess [it] carefully in your trials.”

Dr. Marcel van den Brink

President, chief physician, executive, City of Hope Los Angeles and National Medical Center

“The angle I’ve taken in all of my research is to look first and most of all at the gut microbiome as a manipulator of the immune system, and there are decades of work now backing that up,” van den Brink said. “A simple way of saying it is: The microbiome sets the tone and can activate, dampen or block T cell activation.”

Despite the complicated and voluminous nature of the microbiome’s billions of organisms, van den Brink said the concept could fit relatively easily into a treatment paradigm once fully understood.

“If you think about it, the microbiome is actually much easier to target than other areas within your body, and I think what we’re going to see in the next few years is ‘diet as a drug,’” van den Brink said. “Diet, in my view, is still not taken seriously and lives in places like health food stores.”

Even small changes to the diet can have a big impact, he said.

“Studies we have done show if you change your diet a little bit, your microbiome changes within 48 hours,” van den Brink said. “And if you then realize that the microbiome has very close interactions with the outcomes of checkpoint blockade [immunotherapy], CAR-T cell therapy or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, for example, it is actually a much easier therapy than coming up with new drugs.”

One treatment for an unbalanced microbiome is the introduction of healthy microbiota to the gut, called a fecal transplant. To hone this approach in the case of patients undergoing a bone marrow transplant, City of Hope scientists have sought to define the bacteria that can be beneficial to those patients. Van den Brink said the results so far are promising.

“In the microbiome field, I see two real steps: defining the composition of bacteria and approaching diet as a drug,” van den Brink said.

Establishing prevention in cancer care

The biopharma industry has focused primarily on specific functions of immunotherapy that are tried and true. A monoclonal antibody blocks a particular pathway that calls on the immune system to fight a tumor. An edited gene will allow the creation of proteins that a patient lacks. But van den Brink sees a wide ocean of possibilities when that focus is expanded.

“Anybody who is doing any kind of cancer therapy and development wants to know cardiac function or kidney function or pulmonary function because they know it’s going to impact whatever therapy they’re testing,” van den Brink said. “The microbiome is another organ that needs to be taken seriously — it’s the last organ we have discovered, and you need to understand what the function of that organ is to assess [it] carefully in your trials.”

As pharmas and biotechs study new drugs, they would be remiss to discount that impact, he said. And part of incorporating the gut microbiome into treatment is to place greater emphasis on detection and prevention.

“Where I feel the whole field can do better is early detection and prevention,” van den Brink said. “Everybody preaches it as part of their mission statement, but it’s difficult to do because we have a healthcare system that’s set up to favor treating over prevention — that’s the biggest unmet need in all of cancer.”

Winning the war

The ACS statistics paint a picture of incredible progress in the fight against cancer, van den Brink pointed out. But with more than 2 million new cancer cases projected in 2024 for the first time ever, particularly among younger patients, the scope needs to grow.

One unknown is the cause for the rise of colorectal cancer incidence among younger people, according to the ACS.

Research at institutions like City of Hope, Memorial Sloan Kettering, MD Anderson, the Mayo Clinic, Dana-Farber and more have changed the cancer paradigm, he said. Therapies are being developed faster than ever, and this is the right time to bring younger patient groups into specific studies in colorectal cancer, van den Brink said.

“We need to focus on studies that try to detect these high-risk groups — prevention and screening is more relevant than ever,” van den Brink said, pointing to a City of Hope project led by Dr. Cristian Tomasetti to develop a blood test for early detection of cancer.

Beyond a younger cohort of patients, minority populations also demand more attention from those developing screening, prevention and treatment methods, van den Brink said.

“We deal with many different patient groups, and the other area we have to continue to stay focused on is minorities,” van den Brink said. “If you see these numbers for cancer among Black patients, it’s really terrible.”

Van den Brink works closely with City of Hope chief scientific officer Dr. John Carpten, who joined the institution last year and specializes in healthcare disparities in cancer.

As Carpten and van den Brink build the City of Hope national network, clinical trials are at the center of the vision, van den Brink said. And prevention trials will be part of that outward expansion.