Welcome to today’s Biotech Spotlight, a series featuring companies that are creating breakthrough technologies and products. Today, we’re looking at CymaBay Therapeutics, which is developing a treatment for liver diseases including primary biliary cholangitis.

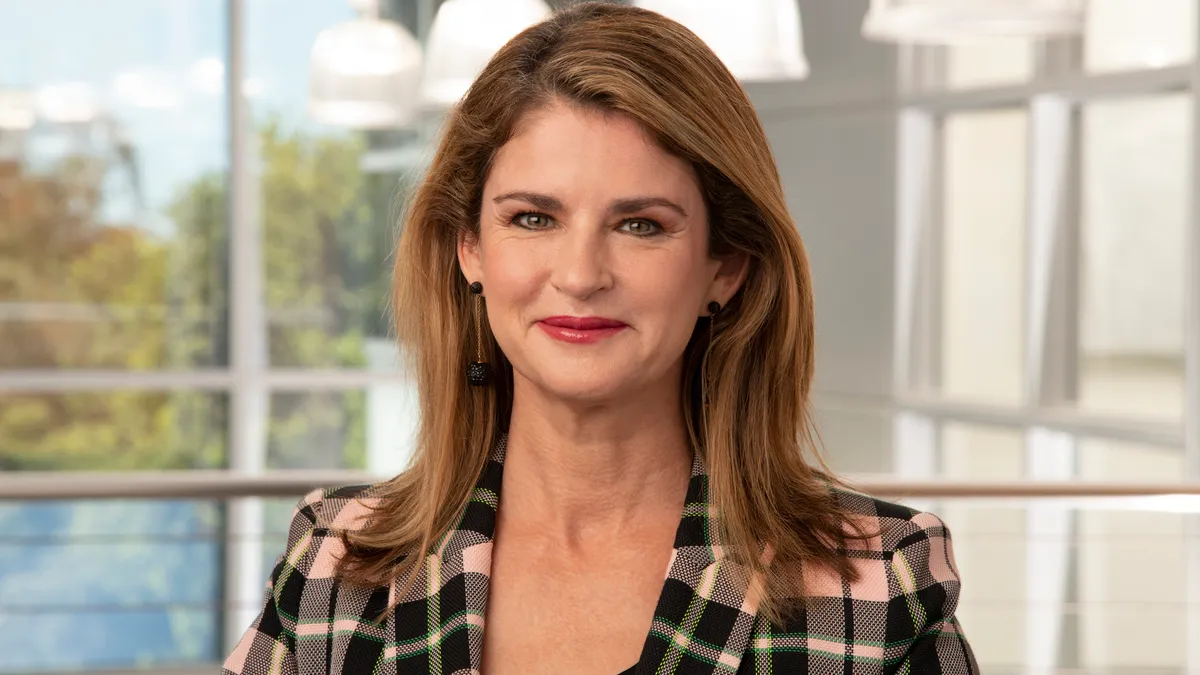

In focus with: Charles McWherter, chief scientific officer and president of R&D, CymaBay

CymaBay’s vision: CymaBay Therapeutics is no stranger to the ups and downs of drug development in a tricky disease space. The biotech’s leading agent seladelpar is now in phase 3 for the liver disease primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and showing strong results that indicate an effective treatment.

Why it matters: Like many others developing drugs for liver diseases, CymaBay had to overcome a particularly disappointing speedbump with a clinical failure in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in 2019. But after a panel of independent experts found the drug showed no evidence of liver damage, the company built seladelpar back into a leading clinical candidate for PBC, a chronic condition that can trigger the destruction of bile ducts in the liver.

Although drugs like Intercept Pharmaceuticals’ Ocaliva can help break down toxic bile in the liver, there’s still no cure, and PBC has other unmet needs. Companies like CymaBay and Genfit are now developing treatments that target the metabolic source of the disease.

"You need to consistently use your capital in a smart way to create value. But sometimes the most expensive thing you could do is not spend money."

Charles McWherter

Chief scientific officer and president of R&D, CymaBay

Here, CymaBay’s chief scientific officer and president of R&D Charles McWherter discusses the winding road that leads to today’s seladelpar targets, how he and the company made the decision to switch gears after NASH and what it takes to make it in today’s biotech market.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

PHARMAVOICE: Liver diseases are notoriously difficult to treat. How did you arrive at the targets that you ultimately came to?

CHARLES MCWHERTER: That’s a very long answer, but the delpar class originally was thought of and still has significant activity for treating mixed dyslipidemia, which includes patients who have elevated triglycerides, LDL cholesterol and maybe lower HDL, or good cholesterol. And so, we conducted a fairly extensive phase 2 study looking at those parameters, and we noticed that we were improving these cholestatic markers. Our discussions with the FDA were happening at the time when PCSK9 inhibitors were just coming to the forefront and fish oil components were being developed for triglycerides — it’s highly competitive and very expensive for a small biotech to develop in that space, and the FDA was telling us we would need a pre-approval outcome study, which would be hundreds of millions of dollars. So we were very excited and intrigued about the effects on cholestasis, and that’s really how we pivoted and decided to take seladelpar into development for PBC.

CymaBay has turned away from development in NASH, which is where trial failures amount very easily. How do you move past that and keep the momentum going with the same compound?

NASH is of course an extremely important public health issue, but drug development is expensive and takes a long time. There are no approved therapies. So there’s not a lot of clarity around a whole host of issues for development, including reimbursement for what will likely require combination therapy. And when you take that into account, it’s very challenging for a small company like CymaBay to think about NASH, even though we saw a good signal for disease activity. We made the decision that allowed us to have the most impact for patients by going after something that was more feasible for us.

After learning that NASH was no longer going to work for you, how did you approach your team with an eye toward the future?

That was a particularly challenging time because we shut down the entire program until we figured out that the findings we had in NASH were actually existing at baseline prior to treatment. It takes a real commitment to do the right thing. The most important thing was the profile of the drug and our commitment to doing high-quality drug development, to communicate that with all the stakeholders, medical experts and investigators involved in our sites — we had formed close relationships and communication channels with patient advocacy groups.

Recently, your stock price jumped as investors appeared to see seladelpar as better suited for PBC than Genfit’s competing compound. Can you talk about that dynamic and what happens down the road?

We continue to point to the results we’ve had with seladelpar with improvements in cholestasis, where we saw about a 67% to 70% improvement in the composite endpoint. So what are investors and the medical community seeing as a profile that’s been reproduced? It shows clear differentiation from the currently approved second-line treatment Ocaliva (from Intercept). I can’t speak much to the results from elafibranor (from Genfit) — they’ve only described the primary endpoint which was less than they had seen in their phase 2 study — but perhaps people are gaining an interest in seladelpar as a step forward if the results are confirmed. The other thing is, we never take the eye off the ball in talking about safety. It’s the totality of the clinical experience and the consistency in the profile. That promise is what I would imagine investors are taking note of.

As you work on other indications, is NASH something you could go for again?

I don’t think it’s on the top of our list right now. One never says never. But I do think that for us to contemplate coming back to NASH, it’s probably not on the horizon for seladelpar. But it’s an area where we’ve developed a lot of expertise not only in the underlying biology but also in clinical development. So if we had the right opportunity where we thought something could be transformational, it’s something we could consider.

How do you define your company in terms of maintaining a balance between focusing on certain areas where you have a solid footing while finding diversification in the marketplace?

The most important decision you make is what to work on. That focuses you and keeps you on a path that’s going to have long-term indications. For us, our scientific acumen is in inflammation, metabolism and fibrosis — therapeutic areas that make sense and come into play with respect not only to medical expertise by clinical development. Then you think about the regulatory path and your understanding of how development would be evaluated. We don’t currently pursue biologics, but I think that’s an area where there’s a lot of expertise and building out in that area would make sense for us. Things like cell therapy and gene therapy are probably not areas that would fit with CymaBay — it’s a big lift, and I don’t think shepherding a drug to patients in those areas would make sense.

With the biotech market downturn in recent years, how do you keep the capital runway clear?

CymaBay has been in existence for more than 30 years, and the first thing you have to be is responsible and efficient. You need to consistently use your capital in a smart way to create value. But sometimes the most expensive thing you could do is not spend money. And so we’ve cultivated and fostered important relationships with the investment community for quite some time. In a downturn, the scramble for resources and investment only gets more intense in what is already a very intense sector.