Editor’s note: This story is part of our 2022 PharmaVoice 100 feature.

It takes a pirate's whimsy to name a cutting-edge biotech after the endearingly resourceful Captain Jack Sparrow from Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean. But that's just what David Katz did in 2013 when he founded his rheumatology- and endocrinology-focused company Sparrow Pharmaceuticals, where he is the chief scientific officer.

"I kind of stumbled into my career at a couple of stages, but it turned out well," Katz says.

He spent 18 years in Big Pharma as a leader in personalized medicine, drug discovery and clinical trials — at Abbott and then AbbVie when the pharmaceutical company spun out — before his sudden retirement at the age of 50, when he decided to strike out on his own, sailing for entrepreneurial shores.

His exit from the pharma giant came at a time when a project he was working on was heading for termination for reasons that Katz disagreed with. He voiced those objections to top executives before announcing his retirement.

"Being a person who sometimes has a bit of a flamboyant streak, I decided to go out in a somewhat flamboyant way," Katz says.

But Katz wasn't done with drug development, and shortly thereafter he founded Sparrow with the intention of finding programs that bigger companies had shut down — whether for strategic or financial reasons — and carrying the torch to the finish line.

"There are compounds and new investigational drugs that have been shelved by Big Pharma for what a scientist or a clinician would call bad reasons, what a business person would call strategic reasons," Katz says. "Investors in large public pharma companies don't place any value in anything that's more than a couple of years from the market."

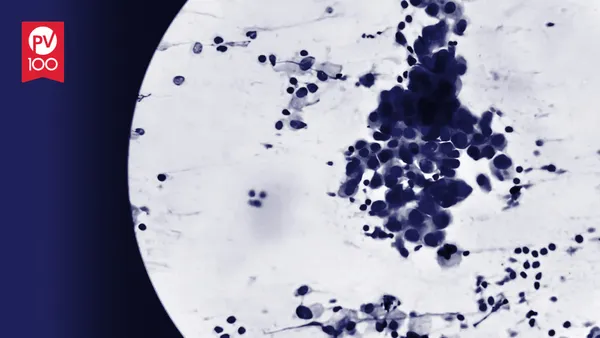

Soon, Katz obtained the license to what is called an HSD-1 inhibitor from Japan's Astellas Pharma — the platform is based on the idea that inhibiting an enzyme called HSD-1, which converts the inactive steroid cortisone to its active version called cortisol, would reduce the adverse effects caused by toxicity from excess cortisol or steroid medications.

That platform seeks to treat patients with autoimmune diseases like polymyalgia rheumatica, which causes stiffness and pain in the muscles around the shoulders, neck and hips, with a drug candidate called SPI-47. The company is also looking to treat the endocrine disorders Cushing's syndrome and autonomous cortisol secretion with its therapy SPI-62. All candidates are in phase 2 clinical trials.

Through his journey from Big Pharma to small biotech, Katz sees how the different cogs fall into place.

"The Big Pharma companies provide incredible learning opportunities because you really learn how to do drug discovery and development," Katz says. "What's evolved in the industry now is something that makes a lot of sense, which is that the big companies focus, to a greater extent than they used to, on the things that are their core competencies — which are making drugs, selling drugs and global operations."

Companies like AbbVie effectively tackle the challenge of conducting a 2,000-patient phase 3 program across 15 different countries and achieve suitable uniformity, Katz says, and that's where their size is an asset. But for Sparrow, the focus remains on the early science without having to concern themselves with later-stage studies, manufacturing and sales.

"With the greater movement over the last few years to venture-funded small companies to do preclinical and early clinical development, with much of that tending to move into Big Pharma later, I think that's actually a rationalization of the industry,” Katz says, “and probably better at matching capital and matching competencies to the different stages of drug development.”

An artist's vision

Like many in the industry, Katz is a scientist at heart with passions for chemistry, immunology and clinical development. But that's not where it all ends, as Katz also pursues a life in the arts — specifically in glass work and theater.

Science and art aren't two completely distinct frames of mind, however — Katz's glass sculpture work brings some of the same skills and outlook required in his day job at Sparrow.

"I think about a clinical development plan and putting a sculpture together as analogous activities," Katz says. "You start with an almost endless set of possibilities — you use your skills, you rely on your colleagues, you get to this end product, but the whole time you have to think, 'What's the goal in mind?'"

The fragility and intricacy of glasswork compares well to the delicate and complex drug development process — but Katz also derives another metaphor between the two: tenacity.

"I had a vase that I made that was sitting up on a windowsill at the top of the staircase in our old house, and one day, it got knocked off and tumbled down the stairs, hit the wall — it made a big hole in the wall, but the vase was fine," Katz says. "I later gave that vase as a gift to a colleague who had shown particular tenacity in a project — because he had to put some holes in walls. Metaphorically."

"You can be very successful and find fulfillment as an entrepreneur, or you can find success and fulfillment in Big Pharma or academia — different people are going to find it in different places, so know yourself."

David Katz

Chief scientific officer, founder, Sparrow Pharmaceuticals

Katz also spent the sabbatical between his retirement and the founding of Sparrow as the managing director of a professional theater company. That's where he learned important lessons about leadership and collaboration.

"Theater is a good place to learn teamwork and how to work without a safety net," he says.

Entrepreneur's spirit

Striking out on your own isn't for the faint-hearted, Katz says, and it involves deep introspection and self-awareness.

"One misconception that I hear from people who aren't entrepreneurs is that somehow it's easy," Katz says. "One of the most important things about being an entrepreneur is you always have to be willing to learn because you're going to have to do things that are outside your comfort zone — you have to be flexible and willing to jump in wherever you're needed."

And finding the right people to be inspired by has been an important step for Katz to take in this journey.

"In the first few years at Sparrow, I had 18 years of experience at Abbott and AbbVie in personalized medicine and drug discovery and clinical development, but I knew nothing about business development, about fundraising," Katz says. "At Sparrow it was first prospecting for the right asset, acquiring the rights for it and going out to get financing to actually support the clinical development."

Mentors on the business side of operations included Gayle Kirkpatrick, who led business development at Abbott and AbbVie, and Bruce Galton, who had served as the CEO of several biotech companies. He also attributes some of his business acumen to late nights with colleagues from across the industry at the MATTER Chicago healthcare incubator.

"They weren't necessarily developing pharma companies, but we used to just sit around with maybe a little alcohol, a group of startup CEOs and entrepreneurs, and it doesn't matter what industry you're in — the problems you're facing are analogous," Katz says.

And of course, Katz still takes inspiration from the pirate Captain Jack Sparrow as he leads his company toward the horizon.

"I like his leadership style," Katz says. "There are no boundaries, and he's very spontaneous, but he's also very effective, and he just has that insouciance where everything rolls off of him — I think that's a great way to lead."