From diabetes medications to chemotherapies and antibiotics, drug shortages are wreaking havoc on the U.S. healthcare system, leaving patients, practitioners and even top regulators wondering: How do we fix this?

“I did not come back to the FDA to spend all my time on supply chain [issues] but that's what happened,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said at a public forum hosted by the Alliance for a Stronger FDA on Wednesday, adding that he’s “pretty fired up to do something about it.”

Fixing the shortage crisis hasn’t proved easy, though. Many drugs have been vacant from pharmacy shelves for months, and in July the number of medications in low supply reached a 10-year peak, according to a report from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Leading causes of the shortages — including foreign manufacturing, lack of supply chain oversight and declining investment in the generics industry — also persist, and tackling these challenges will likely require more might than one agency can muster.

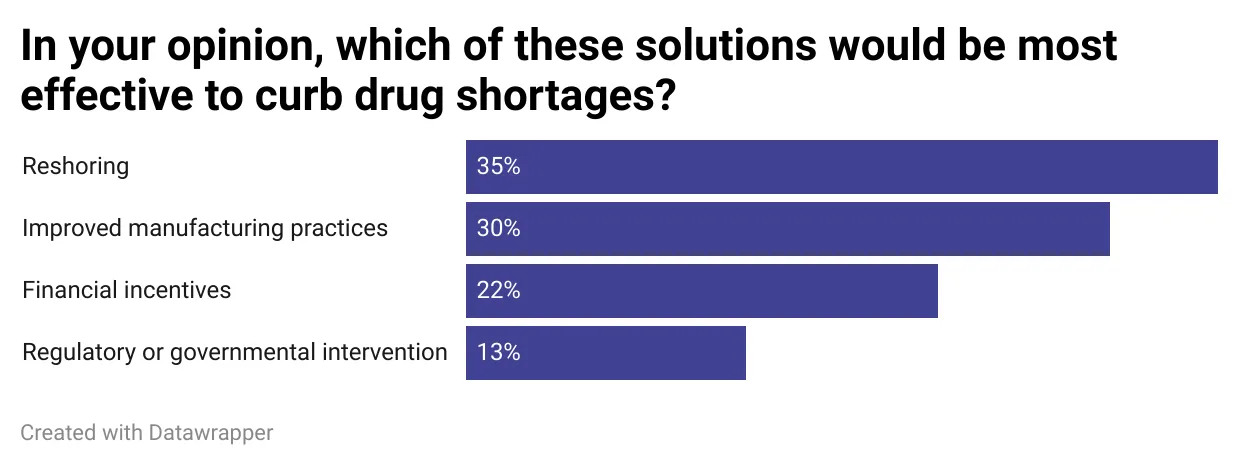

In an informal poll conducted this week in PharmaVoice’s daily newsletter, readers overwhelmingly said some of the most effective potential solutions to curb the shortages included reshoring and improving drug manufacturing.

Califf advocated for similar solutions, highlighting the decline in generics production as a leading cause of the shortages.

“The fundamental problem is that we essentially have two drug industries in the U.S.,” he said, arguing that prices are too high in the “innovator industry” and too low on the generic side.

“The price has been driven down below the cost of manufacturing and distributing the drug,” Califf said. “And we have an industry which is continuing to leave the U.S. because it's not viable to run the business.”

Around 90% to 95% of generic sterile injectable drugs are developed using ingredients made in China and India, according to a recent Senate report. And as prices erode, the investment outlook in the generics industry has also soured.

For Teva Pharmaceuticals, one of the world’s largest generics producers, the rocky landscape has led to a decrease in the production of older generics and in the development of new ones. Earlier this year, the Israeli company said it would introduce generics for just 60% of drugs going off patent, down from its prior goal of 80%.

Similarly, pharma giant Novartis announced plans last year to spin off Sandoz, its generics drugs division, amid declines in the sector.

FDA’s role

Califf argued that a “modification in the market” is needed but acknowledged “it's not the FDA’s job to fix.”

Where the regulator does come in, he said, is in “plugging the holes” when a shortage occurs. However, he added that the agency currently lacks the authority to preemptively request information before supply issues become dire.

"The fundamental problem is that we essentially have two drug industries in the U.S."

Dr. Robert Califf

Commissioner, FDA

“I describe it to people as if we're running a country where every company has its own set of railroad tracks,” Califf said. “They intersect, but no one knows exactly where they intersect and there's no switching mechanism between the companies.”

In other words, the agency has low visibility when it comes to the pharma supply chain.

Last month, Congress moved to address the problem in a bill reauthorizing the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act with a measure that would have required drug manufacturers to notify the agency six months before expected interruptions or stoppages in the production of drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients. The measure failed to emerge from a divided House committee.

The European Union suggested a similar policy in its sweeping pharma legislation that was blasted by industry groups that said it is impossible to predict supply chain issues months in advance.

With low odds of receiving extra oversight authority, Califf said the FDA is working to improve its site inspections and quality management framework to ensure companies are operating appropriately and reducing redundancies in their supply chain.

As far as long-term solutions go, he suggested that “like the banking industry, ultimately over time, we're going to need to have a way for a government agency to delve in and do stress testing, and when there's an impending shortage, intervene.