The H5N1 avian flu infected two California dairy workers last week, bringing the total number of human cases in the U.S. to 16. The new cases are part of an ongoing outbreak that’s remained minimal in humans but spread more widely in livestock across the U.S. since March.

Meanwhile, a cluster of eight possible infections in Missouri has raised fears of possible human-to-human transmission, but testing for H5N1 antibodies among those affected is still ongoing.

Although this avian flu strain has been in circulation for decades, the latest outbreak has grabbed headlines because the virus is moving in “concerning directions,” said Katelyn Jetelina, a well-known epidemiologist and data scientist. After the U.S.’ largest and longest outbreak in birds in 2022, the virus made the jump to mammals, infecting seals, mountain lions, foxes and eventually cows this year, she said.

“That's a big deal, because we've never seen it in cows before,” Jetelina said. “Because humans are so closely connected with dairy cows … it has more ability to jump and mutate. ”

Jetelina launched a newsletter dubbed “Your Local Epidemiologist,” in March 2020 to “translate” public health science for lay people in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. The newsletter’s popularity has since exploded, now reaching more than 230,000 readers in 100 countries, helping Jetelina land a spot on Time’s 100 Most Influential People in Health list earlier this year.

Here, Jetelina talked about the current H5N1 outbreak, the public health response and what’s next for vaccinations.

This interview has been edited for brevity and style.

PHARMAVOICE: The current spread of H5N1 has baffled scientists in many ways, including its jump into different species. But the CDC maintains that the threat level to humans is low. When’s the tipping point for being more worried?

KATELYN JETELINA: A lot of us are not happy with any of these signals we're seeing right now. There's a lot of concern among immunologists, epidemiologists. Our alarm bells are going off. It doesn't mean the general public’s alarm bells have to go off.

Human-to-human transmission is the first building block to fall if this is going to turn into an epidemic or a pandemic. So far, it's not happened. We have concerning information coming out of Missouri that there's a cluster of possible human cases, but we're waiting on blood tests that are currently pending right now to see if there's truly human-to-human transmission. So we're all holding our breath and crossing our fingers. We don’t know yet. … They could all just have COVID.

Death rate reports have been varied. Is there a consensus on what it is?

No. This is really hard because you'll see this 50% fatality rate cited, and technically this is correct because it's what's listed on the WHO’s website. However, the quote-unquote ‘true’ fatality rate is likely lower for a number of reasons. One, is [that the] 50% [rate] is among cases detected. Past antibody studies have shown we are missing many [recorded] infections, and there may even be asymptomatic infections. Two, when viruses mutate for human-to-human spread, they have to make tradeoffs. And usually the tradeoff a virus has to take is trading disease severity for transmissibility. So if this mutates for human-to-human transmission spread, it is likely going to decrease the disease severity. The third reason we don't know the true fatality rate is that we may have some cross protection with regular flu strains.

Regardless of whether it's 50% or 5%, we learned during COVID that even a small percentage of a large number is a large number of people. It could still be devastating.

How has the public health response been so far in the U.S., in your opinion?

It's been hard to watch. On the heels of the pandemic, we would hope that losing 1.5 million people would change things, but it doesn't seem like it has changed much. There's still this initial slow response. There is confusion, frustration, lack of communication between agency coordination — for example, between the USDA that deals with animals, and CDC and Department of Health and Human Services that deals with humans.

It’s also starting to show our fragmented public health system that we haven't really fixed. It's codified into our law that public health is local. All public health powers [lie] within the states. We can debate whether that's good or not, but what is clear is that when we have an emergency or response across states, it's incredibly challenging to get information rapidly and bring the public along for the ride. [There’s added to the] complexity of having to deal with animals and humans, [which wasn’t the case] with COVID. I wish we could be more coordinated and show a united front with a united voice and be proactive rather than reactive, [as] we tend to always be in public health.

What does preparing for the worst look like?

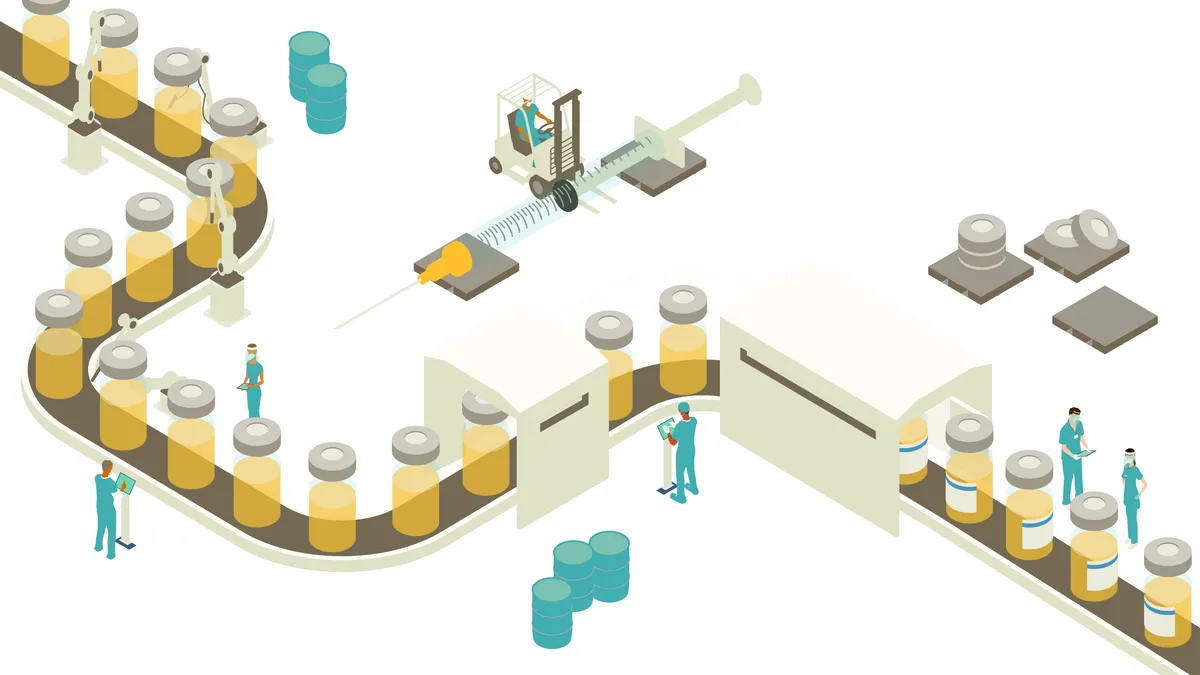

On a national level, that means the FDA has started getting vaccines prepared and getting a stockpile ready. The FDA is going to be holding a really interesting meeting [on Oct. 10] about when and how to start H5N1 vaccines.

On the ground, I would love to see more testing, more visibility into how big this outbreak has been and where it's spreading. We are basically flying blind right now.

How good is our vaccine stockpile?

About 5 million that have been manufactured in the stockpile, and that was done over the summer in a proactive manner, which is great. The question is: When do we start vaccinating people? Finland already started vaccinating those at high risk. The [other] question is: How well do they work? I have not seen any data to show how well they work with this new strain that's transmitting among cows. But anything is better than nothing … so we're optimistic it'll help with at least severe disease.

I'm very curious about the direction the FDA will take [with vaccination recommendations]. Because the truth is, we're not seeing severe disease among farm workers. In fact, they are just getting a little bit of red eye. We only had one severe case, but she had incredible comorbidities over in Missouri. [So] what would be the purpose of vaccinating? And not only that, but the feasibility of vaccinating, too, given such low trust with the highest risk group.