When Luxturna was approved in 2017 to treat a rare form of inherited vision loss, it became the first one-and-done therapy targeting a disease caused by mutations in a specific gene. Despite the historical achievement, there was a problem. The patient population was tiny, topping out at around 2,000 in the US., and the drug had become the priciest therapy on the market costing $425,000 per eye.

Although gene therapy holds promise for rare diseases, current therapies target small patient populations. But a Pennsylvania-based biotech company Ocugen is hoping to change that paradigm by working on therapies that it calls “gene agnostic,” using a first-in-class modifier gene therapy platform with the potential to treat a range of genetically diverse inherited retinal diseases.

“It’s not gene specific like CRISPR or traditional gene therapy,” said Shankar Musunuri, CEO and co-founder of Ocugen. “We are embarking on something really big that nobody has done before.”

Reaching a larger patient population

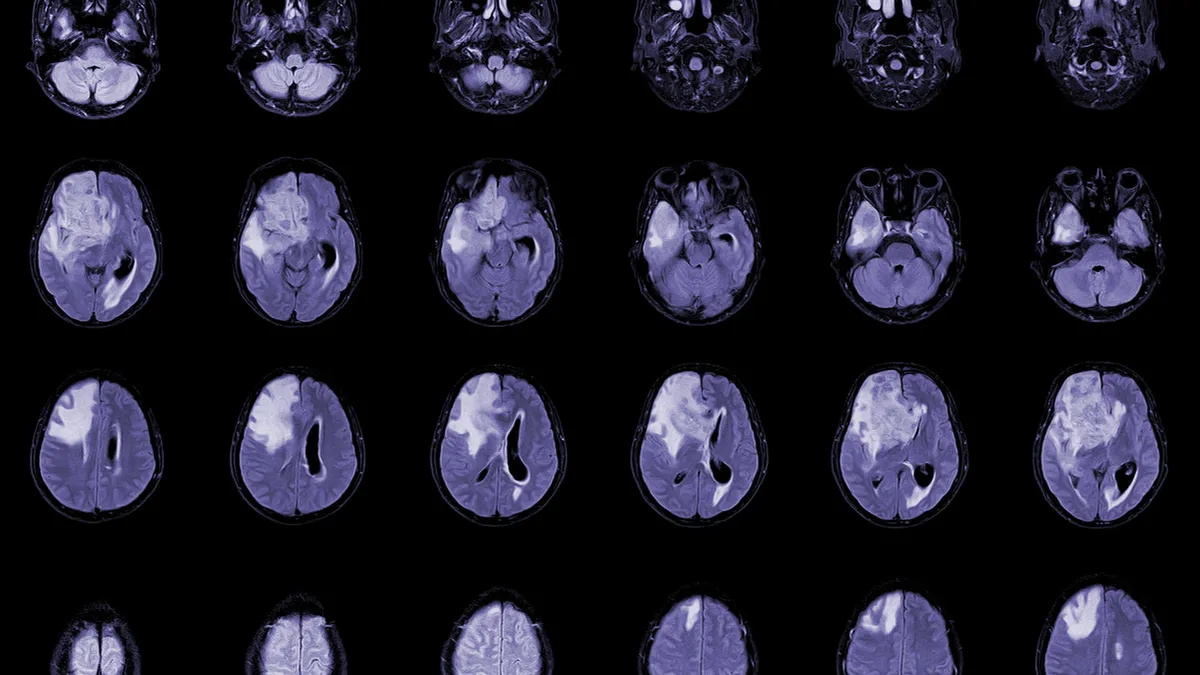

Although Luxturna’s approval paved the way for other gene therapies, it also only treats patients with a mutation of RPE65. However, there are hundreds of genes that cause inherited retinal diseases.

For example, people with the RPE65 gene mutation represent just 0.3%–1% of all cases of retinitis pigmentosa, the most common type of inherited retinal dystrophy, according to a 2023 article in the journal Pharmaceutics

“There are more than 100 genes which can cause RP. There are about 100,000 patients in the U.S. alone, about 1.6 million globally,” Musunuri said.

“We are embarking on something really big that nobody has done before.”

Shankar Musunuri

CEO, co-founder, Ocugen

Ocugen’s lead candidate is OCU400, a modifier gene therapy targeting two families of inherited retinal diseases: RP and Leber congenital amaurosis. It works by delivering a functional copy of a nuclear hormone receptor gene called NR2E3 to target cells in the retina, resetting “retinal homeostasis, potentially stabilizing cells and rescuing photoreceptor degeneration,” the company said.

“If we can reset the homeostasis, restore the function and also create a healthy environment, that’s important for long-term vision restoration. It’s not just fixing one gene,” Musunuri said.

Earlier this month, the FDA cleared Ocugen to initiate a phase 3 clinical trial of OCU400, which also received orphan drug and regenerative medicine advanced therapy designations from the FDA. The company is targeting a 2026 approval.

Ocugen has other gene therapies in development as well, including a candidate for dry age-related macular degeneration and another for Stargardt disease, both of which are in phase 1/2.

Beyond gene therapy

In addition to its specialty in gene therapy, Ocugen is investigating how its platform could be used in other therapeutic arenas.

“Our focus is primarily gene therapy, but these other technology platforms can do a lot of good for patients,” Musunuri said. “We’re focused on unmet medical needs. All the areas we’re working on have significant unmet medical needs.”

One of its most developed assets is on the cell therapy side. Called NeoCart, the therapy treats articular cartilage defects in the knee and was picked up through a reverse merger with Histogenics in 2019. The phase 3-ready candidate is made from a three-dimensional disc of new cartilage grown from patient-derived cells..

Ocugen also has three vaccines in early development for COVID-19, the flu and one being developed as a combination for both. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases will study the covid candidate, OCU500, in a trial comparing administration via inhalation into the lungs and as a nasal spray.

The inhaled vaccines are based on a novel ChAd platform designed to reduce transmission and protect against new variants with long-term durability.

“If you look at the COVID landscape, the current vaccines are not durable,” Musunuri said.

An inhaled, rather than an injectable vaccine, could boost uptake among patients.

“Those are all the salient features which are required for people to be more compliant to take vaccinations,” he said.

A global scope

Musunuri’s career spans from small biotechs to big pharma, including nearly 15 years at Pfizer, where he was global operations team leader for the launch of the blockbuster pneumonia vaccine Prevnar 13.

In the world of Big Pharma, “you do so much, from start to finish,” he said, learning “how to take a product from inception all the way to the market, not just in the U.S. but global.”

He has global ambitions for Ocugen, too.

“Our mission is not just to take these cutting-edge technologies to market. We’re going to work even harder,” he said. “We really want to create market access to patients globally.”