When clinical sponsors develop and submit their investigational new drug applications, several key elements come into play. The first is safety.

“We’re thinking about submitting a new IND for a product that’s going into first-in-human studies, so our focus is on safety,” said Jane Koo, head of regulatory affairs for CTMC, a joint venture MD Anderson Cancer Center and the biomanufacturing company National Resilience to accelerate the development and manufacturing of cancer cell therapies. “So that’s what the FDA is assessing and what we want to ensure for our patients as well.”

Confirming safety includes presenting both clinical and non-clinical chemistry, manufacturing and controls strategies to assure the FDA that patients won’t be subjected to unreasonable risk. Doing so requires cross-functional teamwork, a well-defined process that outlines roles and responsibilities for everyone involved, excellent document control, and clear timelines.

But within this framework — and even outside it — sponsors often descend into several pitfalls, from overpromising outcomes to not taking advantage of opportunities to interact with the FDA.

Here, Koo shares three common IND mistakes and strategies for avoiding them.

Oversharing and overcommitting

The FDA is busy, so INDs should demonstrate safety in the most efficient way possible. Although detail is needed, too many details can be a distraction.

“Something I see commonly is oversharing: Providing too much detail and/or irrelevant information that takes away from your main point,” Koo said.

An example might be providing hypotheses or interpretations of early data that are possibilities, but aren’t supported by further data yet.

“It’s important to be realistic about your process capabilities and [build] flexibility."

Jane Koo

Head, regulatory affairs, CTMC

Providing too much unnecessary information not only creates more work for the FDA but could invite questions and comments from the agency that detract from the IND’s main objective.

Similarly, making lofty promises could lock sponsors into unnecessarily stringent requirements. For instance, Koo pointed to the decisions around acceptance criteria for drug product release. While safety considerations, like sterility, should be the priority, overly strict release criteria could hamper the process.

“It’s important to be realistic about your process capabilities and [build] flexibility,” Koo said. “What you're trying to do … is get your products into the clinic, and if you've got really strict release criteria, it's going to prevent you from being able to do that.”

Neglecting CMC

“It’s important to think about your [chemistry, manufacturing and controls] early on,” Koo said. “We've already seen it for multiple products where FDA action due dates have been delayed due to major deficiencies in CMC.”

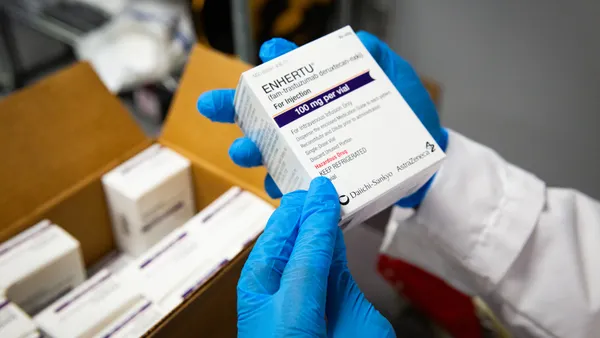

In June, the FDA delayed a potential approval of Rocket Pharmaceuticals' gene therapy, Kresladi, over concerns about its CMC process.

Thinking about CMC early in the process can help sponsors avoid delays later on as they develop comparability protocols.

“That's something you should be thinking about all throughout your development,” Koo said.

While some sponsors “push to have an already commercial-ready process in phase 1,” that’s “probably not really realistic or even actually achievable.”

“It's more important to think about the future by establishing a first-in-human, early-stage process that works, that enables you to move into the clinic quickly but also has the flexibility to smoothly transition into commercialization,” she said.

Over-reliance on published FDA guidance

Sponsors don’t have to rely on just written FDA guidance when they’re preparing an IND. They can also speak directly with the agency.

Pre-IND meetings with the FDA can help “de-risk” the process and perhaps boost the chances of the IND being accepted. However, sponsors don’t always take advantage of opportunities to meet the agency for in-person discussions.

“There are always opportunities to interact with FDA,” Koo said. “Having these kinds of meetings [is] not required. But I definitely highly recommend them.”

In particular, in-person meetings allow sponsors to talk about what they plan to submit in the package. They can also discuss potential challenges a sponsor sees and brainstorm mitigation strategies.

Similarly, sponsors don’t always need to follow FDA guidance exactly if it’s not the best path for their drug. They simply need to be clear about why they’re taking a different route.

“Guidance is guidance,” Koo said.

Because they’re non-binding recommendations, Koo said the FDA knows sponsors are sometimes the most appropriate entities to make decisions about their product.

“You can do things differently, and sponsors should when there’s a good rationale and justification to do so,” Koo said.