Editor’s note: This story is part of our 2022 PharmaVoice 100 feature.

What if we could decode the brain so effectively that drug developers could predict whether a compound will be an effective treatment before they even began clinical trials?

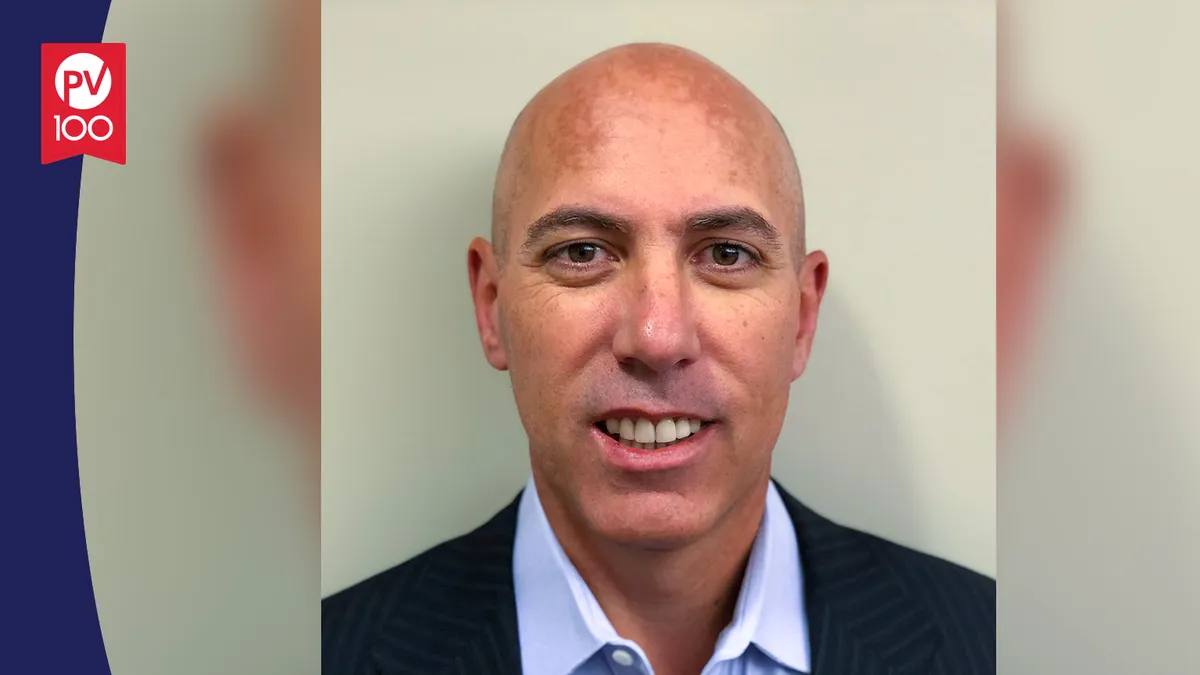

That’s the question that’s been driving Kunal Ghosh, CEO and founder of Inscopix, since a research project at Stanford University resulted in him inventing the “miniscope” — a miniature, integrated microscope that maps brain circuits.

“Right now, we typically go into a clinical trial without a good, mechanistic understanding of how the compound is working. Whether or not the compound will actually succeed is really based on a bunch of clinical trials and statistics. At the end of the day, you have a failure or success decision that’s heuristically based,” Ghosh says. “We can break this unfortunate paradigm very early based on our preclinical data models predicting whether a compound will work before you even go into phase 1.”

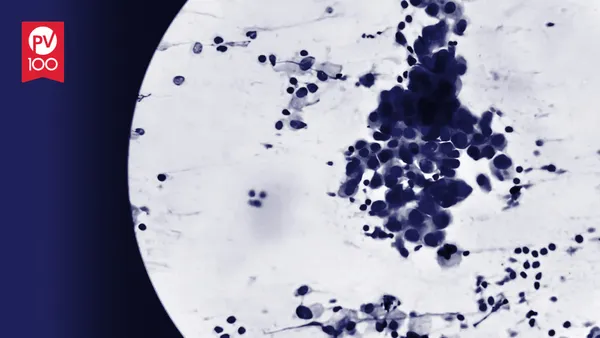

Our brains are made up of billions of neurons that are connected in complex networks. When neurons work together to perform a specific function, that’s a brain circuit, and the way they fire results in different behavioral outcomes. In brain diseases like Parkinson’s for instance, a specific circuit malfunctions.

“A lot of the knowledge is known, but what is not known is how the circuit actually malfunctions, and if we knew that circuit malfunction we could map it, look at what normal is and see what the malfunction is,” Ghosh says. “If we could map those patterns of abnormal brain activity that are the hallmarks of Parkinsonian behavioral symptoms, which we can see in our data, we would be able to develop a data-driven model of the disease and predict if a candidate therapeutic can correct the circuit anomaly.”

That’s exactly what the Inscopix technology does. It works in three steps. First, it maps the brain circuits.

“Our technology lets us look at thousands of neurons in real time. We can literally visualize the activity of thousands of neurons at the cell-specific level so we can extract these patterns of neural activity and we can start decoding the circuit,” Ghosh says.

Next, it classifies the way the circuits are firing.

“Our imaging-based instrumentation allows us to extract these neural activity patterns, and our AI model allows us to classify those neural activity patterns according to normal and disease,” he says.

The last step is screening compounds based on these models and predicting whether a compound has a high probability of succeeding or failing in the clinic by looking at whether the drug is helping to correct the circuit or not.

“We will be able to predict the success of a compound and its therapeutic potential in the clinic very early based on our preclinical models.”

Kunal Ghosh

CEO, founder, Inscopix

“We should be able to either make drugs fail much faster and save a company hundreds of millions of dollars, or advance a promising compound into the clinic with a high degree of confidence,” Ghosh says.

Now, Inscopix is focused on working with pharma clients and collaborators to leverage the technology for drug development. Right now, the company is working on three programs: Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and treatment-resistant depression.

While this sounds high-tech — and it is — Inscopix has a “bootstrap” origin that Ghosh is proud of. He started off building the first Inscopix miniscopes at home, soldering printed circuit boards and cables.

“When we didn’t have the infrastructure, we were building systems at home and leveraging local labs to do some of the more sophisticated testing,” he says. “In the early days these were hand-built brain mapping systems.”

Ghosh also took that “bootstraps” approach to raising money for the company.

“Companies like Microsoft and Google started in that garage-type fashion,” he says. “They didn’t raise a whole lot of money in the beginning. They let their product and their customers do the talking, and then the companies naturally scaled up.”

For instance, one of the first contracts Inscopix scored was with Pfizer, before any venture capital money was put into it. They eventually raised a “very small round for biotech standards,” of $1.5 million in 2011. Collectively, in total, the company has raised only $11.5 million in institutional equity capital, which Ghosh notes is “pretty low” for a biotech company.

But that’s been intentional. Too often, companies get so caught up in fundraising before the science is ready, Ghosh believes.

“The story of Inscopix, in many ways, has bucked conventional wisdom. It has been a bootstrap story,” he says. “It has been a story of having our customers do the talking, having our customers drive the science, and having our customers also drive our business. And I think that has really helped us grow the company, and that has also helped us put science before fundraising.”

The approach has been successful. So far, the company has about 1,000 systems deployed across the world and more than 200 peer-reviewed publications based on the Inscopix platform.

“I’ve always believed that in any healthcare, biotech company — whether it’s in neuroscience or any other space — it’s really important to be patient and let the science let itself out the door,” Ghosh says. “Let the customers and let your science be the proof points, and the business will follow.”