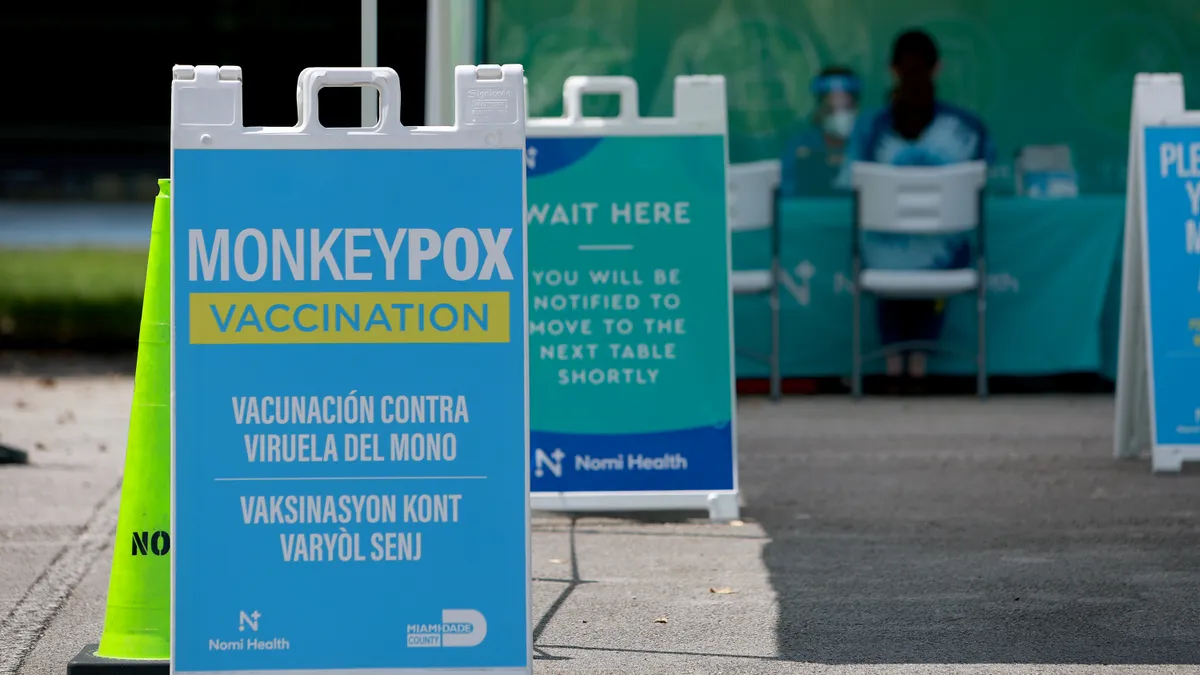

Earlier this year, the U.S. government was scrambling to quell an outbreak of mpox, formerly known as monkeypox. The first known case in the outbreak was identified in a U.K. resident who had recently visited Nigeria, but more cases followed in nations around the world, including the U.S., which was averaging 460 cases a day by early August when federal officials declared a public health emergency.

Contending with a limited supply of the Jynneos vaccine used to protect against the disease, federal officials authorized intradermal injections, a dose-sparing delivery method that helped to stretch the supply. By mid-September, case numbers dropped by nearly 50% and continued to descend. And just last week, on Dec. 14, there were only five new cases reported in the U.S., leading Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Beccera to suggest the emergency declaration likely won’t be renewed when it expires at the end of January.

While federal officials touted a successful vaccination strategy as one of the initiatives that helped drive down case numbers, it’s not clear whether it truly was public health interventions or the natural quirks of the virus itself that led to the precipitous drop, said Stephen Morse, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University.

“Truthfully, we really don't know. Did it stop because of what we did or did it stop because it would have naturally burned itself out?” he said. “And that's an important question, because behind that question is the one that is of concern to me.”

A hidden threat

This outbreak of mpox, which disproportionately affected men who have sex with men, marked the first time there was sustained transmission in countries where the disease isn’t endemic, suggesting that the virus spread undetected for a period, according to the World Health Organization. Previously, cases occurring outside of central and western African countries, where the virus is more common, were tied to international travel or animal importation.

“One of the things that made the size and extent of this (outbreak) possible was probably the way it happened to get into a situation where it could be more effectively transmitted since it requires close contact,” Morse said.

Mpox didn’t get much attention before the 1970s, largely because it was overshadowed by its more virulent relative, smallpox. Vaccinations against smallpox gave people some immunity to mpox, but the virus didn’t take center stage until after smallpox was eradicated and vaccinations ended in 1972, Morse said. Transmission for mpox has ticked up in recent years in part due to the increased susceptibility brought by ending smallpox vaccinations.

Most often people get mpox after coming into contact with rodents or other animals such as monkeys. There’s speculation, but little concrete scientific evidence, that the mpox virus has changed in ways that allow it to sustain itself in human hosts better than past versions of the virus, Morse said. However, sequence data from earlier cases is limited so it’s hard to confirm that an evolution occurred. In other words, it's not clear whether the virus changed or just encountered unique conditions that allowed it to jump from person to person more effectively, causing the recent worldwide outbreak, he said.

Conditions ripe for an outbreak

What is known is that the timing of the 2022 outbreak was unlucky. Not only did it come on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it also arrived at a time when preparedness for a virus of this type had dwindled. Following 9/11, the U.S. was on high alert for a potential terrorist attack using smallpox so it bolstered its defenses to respond quickly should someone unleash the virus that carries a 30% mortality rate on a largely unvaccinated public. There was an effort to create a national vaccine stockpile, which federal officials drew from to respond to the 2022 outbreak, but in the more than 20 years since 9/11, the focus on preparedness had waned and supplies were short of where they should have been when case numbers began to rise.

There are currently two vaccines used for mpox: the Jynneos vaccine, manufactured by Bavarian Nordic, is the main option used and was first approved for smallpox and mpox in 2019. The smallpox vaccine ACAM2000, manufactured by Wyeth Laboratories, was authorized for use in mpox through Expanded Access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol. ACAM2000 is typically not advised for use in people with weakened immune systems or with certain skin conditions, such as psoriasis.

"We had the tools. We didn't put them in place quickly enough."

Stephen Morse

Professor of epidemiology, Columbia University

Another component of the U.S. response included a smallpox antiviral, tecovirimat (Tpoxx) for people who have, or are at high risk for severe disease, which was also part of the national stockpile and permitted for “compassionate use” by the CDC under an expanded access Investigational New Drug protocol.

“There was initially some hesitation to use Tpoxx to treat mpox,” Morse said, explaining that this was due to fears that overuse could make the virus become resistant to the only effective treatment. There is limited efficacy data on how well Tpoxx works against mpox in humans, but the drug does appear to help speed recovery in some people from the often-painful disease.

“We had the tools. We didn't put them in place quickly enough,” Morse explained, noting that there was also a limited supply of the vaccines and antiviral medication. “So that says something about the sustainability and the need to be able to continue investing and sustaining these things.”

Maintaining preparedness

Overall, Morse said that he would rate the U.S. response to the outbreak a B-minus, primarily because it was dogged not only by these shortages, but also by testing delays, and challenges with data sharing and public health messaging.

It remains to be seen how the experience will shape public health initiatives going forward, but it’s likely that staying prepared will remain a challenge for countries.

“I think what's going to happen essentially, is what usually happens when an outbreak ends … people declare victory and go home until the next outbreak,” Morse said.

One of the focuses he said should be on increasing support and vaccinations in countries where outbreaks are more common, and the virus is endemic.

“Maybe this will encourage the high-income countries to do something about (mpox) in Africa, providing vaccines, providing other measures to both prevent and treat those who may be at risk,” he said.

If lessons aren’t learned, the U.S. will likely find itself racing to catch up with the next pandemic, but Morse said he’s hoping instead for a more enlightened and proactive approach.

“Unfortunately, it hasn't happened in the past,” he said. “Hope springs eternal, that’s all I can say.”