Even for the most deep-pocketed drug companies, $14 billion dollars is no small investment. That kind of money can buy large manufacturing plants, offices in glossy skyscrapers and entire campuses dedicated to specific research. But Bristol Myers Squibb has different plans.

Late last year, the pharmaceutical giant agreed to spend that much acquiring Karuna Therapeutics, a Boston-based biotechnology company. Karuna’s most advanced medicine could be approved as a schizophrenia treatment before the end of September, bringing to market for the first time in decades a new form of antipsychotic. Some Wall Street analysts expect the drug to become a megablockbuster.

Bristol Myers sees significant opportunity too, though not yet enough to make psychiatry a top priority. “Failure rates are still very high,” noted Richard Hargreaves, who leads the company’s main neuroscience research center. “That was one of the reasons why neuropsychiatry moved into the biotech industry.”

“The bigger players like Bristol Myers, we watch how [biotechs’ efforts] unfold without actually dedicating big resources ourselves,” he said. “Personally, I'm not seeing us changing from [that] strategy.”

Once a cornerstone of large pharmaceutical firms, psychiatric drugs have been passed over for much of the last 20 years. Developers and investors gave various reasons for the collective retreat, but their decisions ultimately came down to dollars and cents math. Brain research had become too difficult, expensive and risky, and easier money could be made elsewhere.

The pullback has left a void of novel treatments for the hundreds of millions of people with conditions like schizophrenia, depression and substance use disorder.

Now, for the first time in ages, neuropsychiatry is back in focus thanks to the acquisition of Karuna, the potential approval of its medicine, as well as a $9 billion proposal from AbbVie to buy Cerevel Therapeutics, a company working on a similar schizophrenia therapy. While doctors and researchers welcome the excitement and argue it’s necessary to propel the field forward, they also wonder whether the renewed investment will be short-lived, as many of the issues that historically held back this area of drug development remain unresolved.

“The past is a very good predictor of the future,” said Paul Kenny, chair of the neuroscience department and director of the Drug Discovery Institute at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine. “I think pharma more will likely remain skeptical and trepidatious, because that's been the case for at least the past 10 years.”

“I don't know what's going to change that,” Kenny said. “Something big would need to happen.”

Cracking the brain

In many ways, the brain seems straight out of science fiction. A mass of 85 billion nerve cells acts as the body’s control center, directing everything from mood, movement and the senses to how we think, dream and problem solve. It’s the organ that “makes us human.”

Unsurprisingly, it’s also the most complex. Just last year, an international team of scientists identified north of 3,300 cell types in the brain.

Researchers are “only scratching the surface in terms of our understanding,” according to Kenny. “Basically, every week, a new paper comes out [showing us] how cells are wired in ways that we didn't understand before, how they're functioning in ways that we just didn't appreciate.”

For drugmakers, this lack of understanding has brought costly setbacks. In Alzheimer’s disease, companies like Eli Lilly, Roche and Biogen each spent hundreds of millions of dollars investigating medicines that were ultimately unsuccessful in big clinical trials. And in ALS, more than half a dozen potential treatments flunked key studies over the past few years.

In neuropsychiatry, failures are so commonplace that finding new therapies has become, as an article recently published by Nature highlights, “the purview of only a handful of smaller more risk-taking biotech companies and a few academic drug discovery programs.” Karuna is one such example, as its “KarXT” schizophrenia medication is made from a molecule Lilly discarded years ago.

While all drug development is expensive and time-consuming, with very slim odds of success, the challenges are acute in neuropsychiatry. Researchers believe mood and behavior disorders are likely caused by small contributions from a constellation of genes, rather than just one or two faulty DNA sequences. Those tangled roots make choices around which proteins or molecules to target much harder.

Once a target is selected, drugs are designed and then tested in animals to anticipate how they’ll work in people. But these “models” are less reliable in psychiatry, since they assume animals and humans similarly express complex emotions and behaviors. In a mouse, it’s easy enough to see whether a therapy shrinks a tumor or reduces swelling. It’s much more difficult to tell if a mouse's anxiety resembles what a person might feel, or whether such stresses can build into something akin to depression.

“Scientists like me have a lot to answer for,” Kenny said. “We took animal procedures and extrapolated into humans far too readily.”

With such a shaky foundation, psychiatry drug programs tend to fall apart once they move into humans. Most other areas of clinical research are at least able to lean on biological markers that, much like car dashboards do for drivers, signal what’s going on in the body. But scientists have discovered relatively few of these for brain drug development in general, and next to none in psychiatry.

That’s forced clinicians to rely on subjective assessments like surveys and questionnaires, which can be a particular problem in the large, placebo-controlled trials that are the gold standard of drug testing. Over the years, a laundry list of promising treatments for depression and other mood disorders fell short because patients in control groups did better than expected.

Psychiatry studies are “notoriously difficult to do, because you're trying to do everything you can to minimize a placebo response,” said Graig Suvannavejh, an analyst at Mizuho Securities who formerly held business development roles at AbbVie, Biogen and the biotech Alzheon.

“A lot goes into hopefully getting a high-quality trial outcome,” he said. “But in psychiatry, the variables are such that you can try so hard but still not know what you're going to get.”

The task for trial designers is made more complicated by the fact that diagnosing these diseases isn’t straightforward.

People with schizophrenia, for instance, can display a wide array of symptoms, from “positive” ones like hallucinations to “negative” ones like lack of motivation. Simultaneously, they may have other conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder, or be unable to consent and adhere to study rules.

“If somebody has just schizophrenia, that would be the most ideal, clean participant,” said Carol Lim, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital. “In reality … it's a whole spectrum. If you have 1,000 people with schizophrenia, everyone will look different.”

Altogether, the pitfalls and obstacles have given psychiatry drug development an ominous reputation, with some experts describing an impassable chasm between the early science of their labs and the medicines pharma companies want.

Little progress has been made navigating this metaphorical gorge, which is why the KarXT story is so extraordinary.

Finding something new

The journey of KarXT is well documented, as it represents not only a rare win in an exceedingly tough field, but also how central a role luck has played in the discovery of antipsychotics.

In the 1990s, Lilly was exploring whether a drug called xanomeline could improve cognition in Alzheimer’s patients. A nearly 350-person trial showed it had a modest impact. But more surprisingly, researchers noticed the drug seemed to quell the disruptive behavior and psychotic symptoms that often accompany Alzheimer’s.

The findings were especially alluring because xanomeline wasn’t like available antipsychotics — all of which block dopamine, a chemical brain cells need to communicate but is thought to trigger psychosis when in excess. Instead, Lilly’s drug worked primarily by boosting certain “muscarinic receptors,” proteins that are found throughout the body and interact with a different neurotransmitter, acetylcholine.

Though effective, dopamine inhibitors frequently cause weight gain, sedation and other health issues that lead patients to switch medications or stop taking them altogether. A more tolerable option could be highly valuable, so Lilly, intrigued by what the researchers had seen, set up a separate study with a small number of schizophrenia patients.

Again, xanomeline had a positive impact on psychosis. But its reach extended beyond the brain and into the gut, where it caused digestive problems. Because of these side effects, Lilly ultimately shelved the drug until 2012, when Karuna licensed it for the paltry sum of $100,000.

Karuna had hatched three years earlier as the brainchild of Andrew Miller, who was at the time an executive at PureTech Health, the biotech startup creator that got Karuna off the ground. Miller believed xanomeline could still work; it just needed to be coupled with a drug that hindered muscarinic activity outside of the brain. The Karuna team found such a drug, and named the pairing KarXT.

"There was a huge amount of skepticism," PureTech CEO Daphne Zohar said. "Probably 100 investors passed on the idea."

Yet, since 2019, the therapy has succeeded in three medium to large clinical trials. Not only did KarXT significantly decrease the severity of schizophrenia symptoms, it didn’t cause excessive weight gain, restlessness or movement issues, though there were other side effects. Karuna submitted an approval request to the Food and Drug Administration last fall, and the agency intends to make a decision by Sept. 26.

While there have been some innovations in antipsychotics, such as longer-acting shots, KarXT is viewed as a leap forward. “For the first time in 30 years you're seeing novel mechanisms now coming to fruition,” Hargreaves said.

At MassGen, Lim has found patients come to appointments asking about KarXT and eager to try it, based on what they’ve heard about it being effective without causing weight gain.

“It's the first time we're not directly targeting dopamine receptors. So we are avoiding a lot of side effects. That’s a really good thing,” Lim said.

In spite of the anticipation, doctors aren’t sure how much this milestone will actually benefit patients. They note how, in those KarXT studies, the main treatment periods lasted only five weeks and never pitted the drug against another antipsychotic. They’ve also said that, outside the tight controls of a clinical trial, patients might not find KarXT as effective or as easy to stay on.

How readily insurance providers would cover a drug like Karuna’s is another unknown, given the FDA has approved nearly two dozen antipsychotics, many of which have inexpensive generic versions.

“There's so much we don't know in terms of practical usage,” said Mitzi Gonzales, a neuropsychologist and director of translational research at Cedars-Sinai. “You really have to be sure it's better than everything else out there that's cheaper and more readily available.”

Jeffrey Lieberman, a psychiatry professor at the Columbia University Medical Center and a former member of Karuna’s scientific advisory board, foresees KarXT being a “huge” product initially. From there, physicians will closely watch how well the drug works, and whether it can meet their patients’ lofty expectations.

On Wall Street, expectations are equally high. Analysts at the investment firm Cantor Fitzgerald predicted KarXT sales will reach $1 billion a year starting in 2026, while Stifel analyst Paul Matteis has estimated peak annual sales will top $10 billion.

Matteis has also said three other companies advancing muscarinic receptor drugs — Neurocrine Biosciences, Neumora Therapeutics and MapLight Therapeutics — could see more interest from dealmakers in the wake of the Karuna and Cerevel acquisitions.

“The fact that they're just such a completely different mechanism and the majority of schizophrenia patients aren't well controlled, that can lead these drugs to being a really big class,” Matteis said.

Building the pipeline

Beyond muscarinics, a handful of other drug classes are drawing attention back to neuropsychiatry.

Stimulating “orexin” proteins has been shown to help patients with narcolepsy, so companies like Takeda Pharmaceutical, Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Alkermes are trying to speed orexin-targeting medications to market.

Another group of proteins known as “TAARs” are seen as promising targets for treating schizophrenia and other psychoses. The most advanced of these drugs, from the Japanese developers Sumitomo Pharma and Otsuka Pharmaceutical, was recently evaluated across two late-stage clinical trials, but failed to meet the main goals of either.

A gene named TRPC encodes for proteins involved in nerve cell function, and research has suggested inhibiting two of those may be helpful in a variety of psychiatric conditions. German drugmaker Boehringer Ingelheim is testing this hypothesis with a medicine in mid-stage testing for PTSD and major depression. Karuna is invested, too, having acquired exclusive rights to experimental therapies from the now-defunct Goldfinch Bio.

Drug hunters are also revisiting a well-known family of proteins that affects stress, mood and pain. Earlier attempts to regulate these “kappa opioid receptors” led to therapies that were held back by side effects. Cerevel, Johnson & Johnson and Neumora are developing new versions for the treatment of major depression that they designed to be safer.

Arguably the buzziest area of research are psychedelic compounds. Long dismissed because of thorny legal and scientific issues, psychedelics are being taken more seriously as possible treatments for anxiety, depression and psychosis.

Last summer, the FDA issued initial guidance for drugmakers interested in this research — a pool that has expanded considerably since 2019, when the agency granted a first-of-its-kind approval to a derivative of ketamine that J&J developed for depression. That medicine, sold as Spravato, is on track to generate $750 million in annual sales, according to analysts at Jefferies.

Envisioning big returns, investors have been pouring money into psychedelic-focused biotechs. In January, Lykos Therapeutics raised $100 million to support an ecstasy-based medication for PTSD. And more recently, Cybin, a company trying to treat depression with a compound found in many mushroom species, raked in $150 million.

Bristol Myers’ Hargreaves expects the psychedelic field to advance as more drugs get cleared for human testing. “We’ll find new approaches into neuropsychiatry that way, I think as much as anything else.”

On a broader scale, Suvannavejh feels as though he’s seeing an increase in the number of mid- to late-stage trials for psychiatry drugs. The data is “pretty rich” compared to prior years, he said.

Still, psychiatry continues to make up a fraction of clinical research. A recent report from Iqvia, a healthcare services and information provider, found neurology accounted for 10% of all human studies started last year. There were around 60 in both schizophrenia and depression, and far fewer in anxiety and sleep disorders.

“I don't think the pipeline should be as empty as it is, based on our really burgeoning understanding [of the brain],” Kenny said. “We're really feeling the pinch, in the sense that those pipelines don't really exist.”

Keeping hope alive

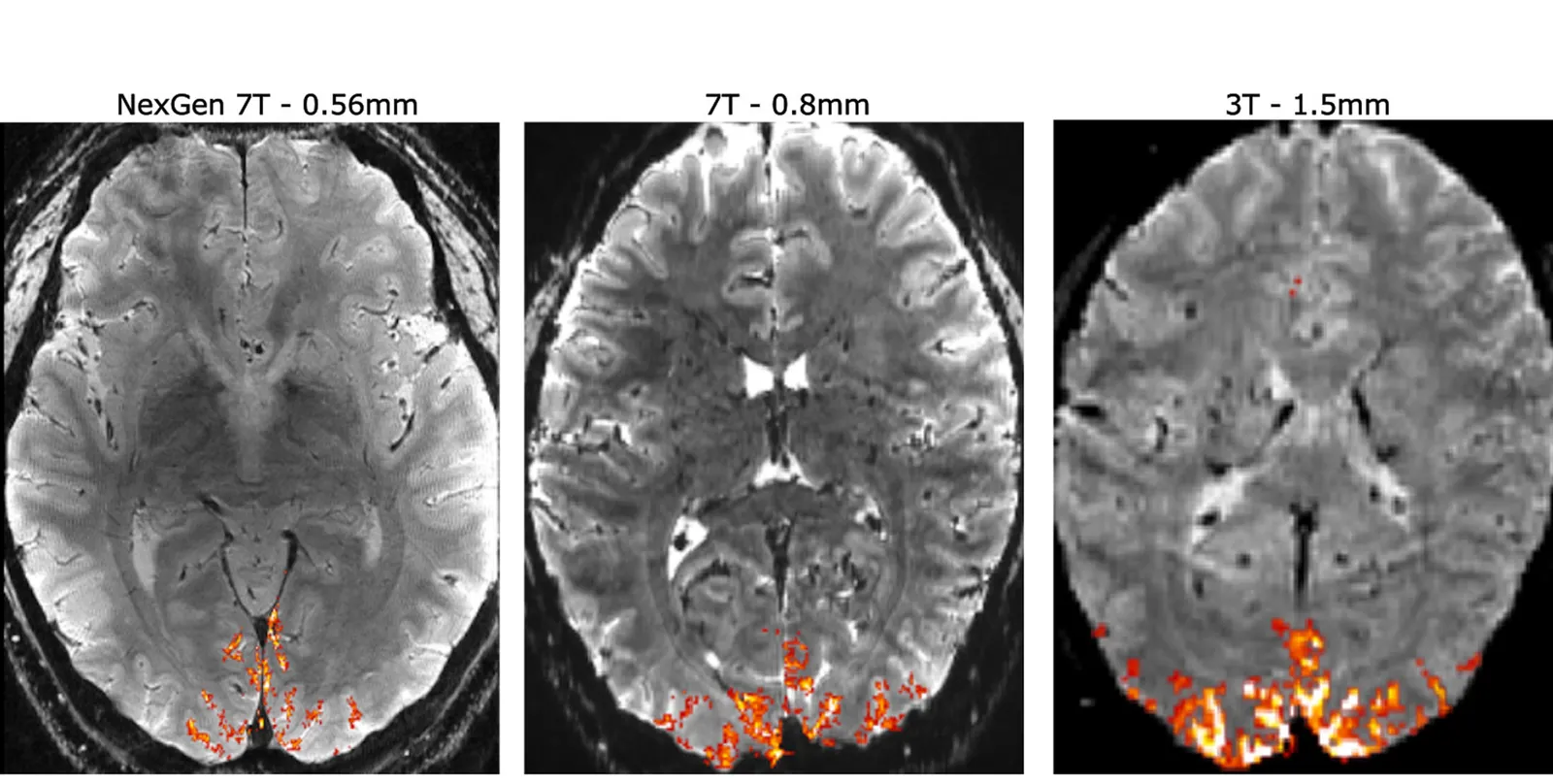

Experts don’t think the pinch will last forever, though. Breakthroughs in neuropsychiatry are already happening, such as the use of light and chemicals to control nerve cell activity. Imaging technologies are improving as well, offering a look at brain circuitry with never-before-seen clarity.

"If you combine imaging together with highly selective chemical tools, which are the drugs, you can begin to understand [how therapies affect] brain circuitry, and which brain regions are involved in which responses," said Hargreaves.

"This has long been a goal in the field, but I think it's become a lot better in recent years."

Bristol Myers is willing to wait, however. Rather than build a large neuropsychiatry organization around Karuna, the company is content to lean on external partners, Hargreaves said.

Other pharmas may take a similar approach. That means smaller, more specialized drugmakers will likely shoulder much of the neuropsychiatry research. Some might argue that could be for the better. Drug programs like KarXT can more easily slip through the cracks at big, multinational firms, which typically split their attention and resources across units dedicated to different diseases.

Whether the presence of these larger companies is necessary for the field to bloom is also a point of debate. Several biotechs, from Intra-Cellular Therapies to Acadia Pharmaceutical to Alkermes, have successfully developed and commercialized psychiatry drugs on their own.

What’s important, according to researchers, is to build on each incremental step and keep resources flowing into the field. “Whenever any [neuropsychiatry] news comes out, I think we have to somewhat get excited, because otherwise there would be no reason for hope,” said Gonzales. “And we have to have hope. We have to invest in the things that look promising.”

For drug developers, the brain represents a final frontier of sorts, much like ocean’s depths or the reaches of space do for other scientists. Cracking it is “not for the faint of heart,” according to Lieberman.

“At the same time, there's a huge unmet clinical need, and tremendous profitability to be had,” he said. “So that's to say, if you're up for the challenge, it's certainly worth the effort.”

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas contributed photo research to this story.