For Dr. Kristina Allikmets, working in a field as specialized as plasma-derived therapies is both a challenge and a privilege. As senior vice president, head of R&D, of the Plasma Derived Therapies (PDT) business unit at Takeda, Allikmets is striving to bring therapies to rare disease patients that have no other treatment options.

The PDT unit was formed at Takeda in 2019 following the acquisition of Shire, and has been led by Allikmets, who’s been with Takeda for 17 years. The complex nature of PDTs led Takeda, the largest drug manufacturer in Japan, to establish a standalone R&D organization to develop the treatment modalities. At the same time, however, the unit benefits from being part of a global R&D organization with extensive capabilities and knowledge.

Today, Takeda is one of the largest players in the rare disease field and has honed its focus on treatments for patients with rare diseases in immunology, hematology, metabolic and lysosomal storage disorders.

“Takeda works on a principle of trying to treat a disease with the most logical and best available modality, be it a small molecule, a targeted biologic therapy, a gene therapy, or any other,” Allikmets says.

Here, Allikmets talks about what makes PDT such a unique field and why Takeda is so well-placed to advance outcomes in rare diseases.

PharmaVoice: What vital capabilities does a large pharma company like Takeda bring to the rare diseases space?

Dr. Kristina Allikmets: Both small and large companies in the rare disease space must, by definition, be patient-centric. At Takeda, the patient is at the center of how we work, and that’s even more important in the rare disease space. We have long embraced concepts such as working with a patient in drug development, rather than for patients in drug development. What makes a big organization powerful is that diseases can be tackled with different modalities. Whether it’s a gene therapy or a targeted biologic therapy, or a plasma derived replacement therapy, Takeda has the capability to address the need, and that gives us a broader opportunity to meet the needs of the patients with those rare conditions.

Can you offer tips and suggestions for other large companies entering the rare disease space?

My first piece of advice is to listen to the patient. In most diseases, drug developers depend on the voice of a treating physician or opinion leaders in the field. But physicians see very few rare disease patients, so, really, it’s the patient who is the expert. By understanding the patient, we can identify things like meaningful endpoints for our clinical trials. Very often those diseases do not have clear regulatory pathways, and again, we listen to our patients to understand the disease modifying effects that we should be measuring for as we move a drug forward to the regulatory agencies.

The second piece of advice is that in rare diseases, probably even more than other areas of drug development, collaborations and partnerships are crucial. That means partnering with patient organizations, or with organizations focused on caregivers, during drug development in terms of what patients need and how to enable them to manage the disease better. It also means collaborating for innovation, whether with academia or smaller biotech companies, wherever the idea generation happens.

What's unique about plasma derived therapies in rare diseases?

The simple answer really is that everything is unique about them, starting with how personal therapies are manufactured, which is from using live human tissue plasma that we collect from healthy donors to manufacture the plasma therapies. So, the therapies that come from plasma, by definition, usually can’t be made in laboratories through the technologies available for today's drug development.

Another very important element is that the diseases that plasma therapies treat are predominantly genetically driven rare disorders where there is a missing protein, missing enzyme or a deficiency that the patient is suffering from. The PDTs are either a single protein or a fraction from plasma, like immunoglobulins, which is a polyclonal mix of different immunoglobulins. These are administered to the patient to replace the deficiency, the missing proteins, that the patient's body cannot produce because of the disease. Since PDTs require donors, we must ensure we collect plasma from those donors in a responsible and sustainable manner.

Can you talk about the ways in which Takeda’s PDT business unit conducts advocacy and outreach with patients?

It starts with a question: How do we serve the patients better? Any decision must always benefit the patient. We focus on patient trust, reputation, and then the business, in that order. The best way to explain this with PDTs is with regards to administration, which involves a huge volume of highly viscous liquid that is not simple to administer. Typically, administration is done intravenously, but the infusions take time, and patients must attend infusion centers or hospitals to get them. And since these diseases are lifelong, it is a continuous burden on patients.

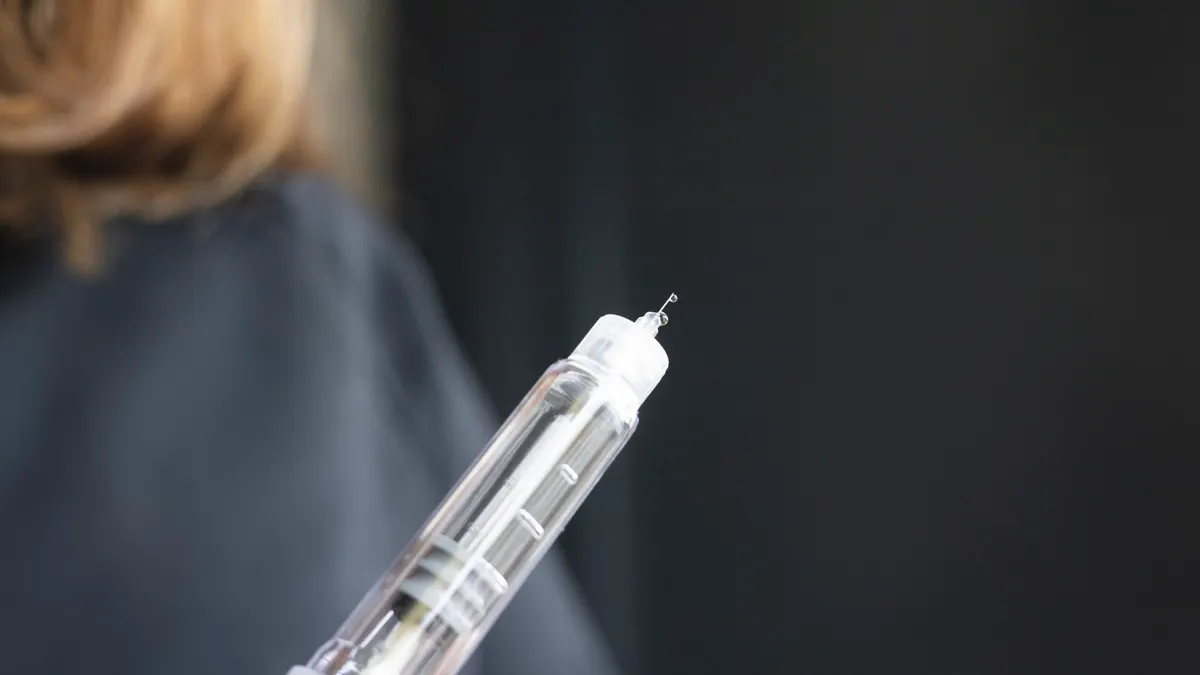

To alleviate this burden, we have focused on developing formulations that can be used subcutaneously, which lets the patient administer the therapy at home. This eases the burden somewhat, but it's still highly cumbersome for them to administer the therapy at home. So, we’re working hard to meet the patients’ needs for simplifying that process. For example, we're launching a device called HyHub, which simplifies the administration of our immunoglobulin therapy HYQVIA.

Another burden they face is getting diagnosed — a problem across all rare diseases. Mineral deficiencies, for example, can be masquerading behind symptoms that are hard to spot for the treating physicians. So sometimes it's years before patients get properly diagnosed and then get the relevant therapy. To address this issue, we work with the Jeffrey Modell Foundation, which, among other projects, is supporting children with immunodeficiencies to get diagnosed so they can get the right treatment when there is a gene therapy available for their particular genetic mutation.

Do you have a personal connection with rare diseases and more specifically plasma deficiencies?

I'm blessed not to have anyone in my family suffering from any such diseases, but I do have a colleague who works closely with the PDT business unit in patient advocacy who has four children who all suffer from primary immunodeficiency. All those children have to be treated continually at home. She has taught me and all my colleagues so much about the burden of care. She is grateful to have the opportunity to get the medicine that helps her children lead normal lives, but there is this constant burden of administration of the plasma therapy at the right time. I’m inspired and humbled by her stories about the immense value that our therapies can bring, but also how much still needs to be done to make it more accessible and easier for patients.