Sonya Miller follows the science. In 2017, she followed it so completely and with such focus into a crowded conference room that she accidentally sat next to the CEO of TauRx Pharmaceuticals and talked herself into a job.

That's when Miller, an anesthetist for 25 years, was working as a principal investigator for several neuroscience trials, one of which was an Alzheimer’s disease study being conducted by TauRx, and she attended a presentation during the investigator meeting held by the company.

"I'm blind as a bat and I'm always late, and the only spot free was right at the front on the side," Miller says. "I was actually next to Claude [Wischik, TauRx CEO] and John Cheung, who's head of development, and I was telling them all the things that were wrong with the trial — and I didn't have a clue."

It turned out one of the missing factors they needed was a doctor to head up the company's trials. Miller was hired as medical oversight lead, and now she also holds the position of head of medical affairs at TauRx.

"Trails are often long and winding and interesting, aren't they? It suited me," Miller says. "I wouldn't work in a massive pharma where things get shut down because of funding or current trends — TauRx is completely focused on neuroscience and always has been, and it's completely science driven."

Miller says TauRx "is really an R&D company that is now becoming more than that, but the science has always been pivotal."

TauRx plans to release interim results from its phase 3 study in Alzheimer's later this month. The study is comparing the company's tau aggregation inhibitor to a placebo for 12 months, and then a year from now, comparing that to people who have had the drug for a total of two years.

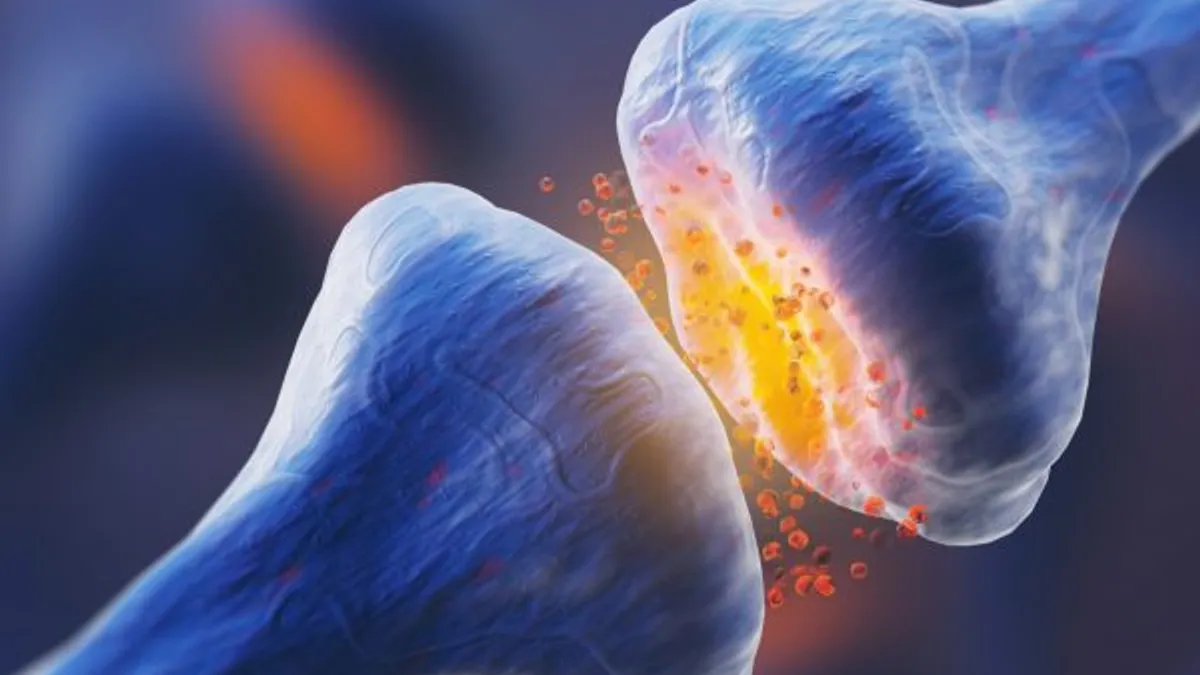

A product of almost 30 years of research, TauRx's potential treatment breaks up the sticky tangle of proteins that build up inside neurons and are linked to Alzheimer's disease. The results of the trial could set the stage for the importance of tau in the therapeutic landscape and ultimate treatment of patients with the devastating condition.

The company is also developing an anti-synuclein compound for Parkinson's disease and earlier-stage candidates for other neurodegenerative conditions.

Tau's promise

Normally, tau is critical to communication between brain cells, but misfolding of the protein causes the tangles, which disrupt brain function.

"These good proteins go bad for a variety of reasons and they become larger and larger until they clump and tangle and destroy the nerve cell function," Miller says. "And this process continues and accelerates, and at a certain point it's like falling off a cliff face, and you deteriorate very rapidly."

Alzheimer's can lead to a patient's death as the result of a loss of brain volume or injury due to a lack of awareness.

"Our focus has always been on tau, and we were considered sort of the outrider early on."

Sonya Miller

TauRx Pharmaceuticals medical oversight lead

In Alzheimer's research, tau is one of two leading biomarkers for the disease, the other being amyloid plaques that also build up in the brain. While tau aggregates inside the neurons, amyloid collects outside the cells.

The search for either amyloid plaques or tau in patients is often driven by external factors like availability of testing and scanning, Miller says, and the specific substances — called radioligands — used to scan for amyloid plaques were developed much earlier than those for tau.

"Tau is really only becoming more mainstream now," Miller says. "All the last 20 years of research, it was more focused on amyloid, and that was more because you could scan and you could see amyloid in the brain lit up with radioligands."

It stands to reason that researchers more quickly developed drugs reducing the amount of amyloid plaque buildup, but this didn't always lead to a change in cognitive function, Miller says. The most recent example of this can be seen in the controversial approval of Biogen and Eisai’s Aduhelm, which did reduce amyloid plaque but had conflicting clinical outcomes in late-stage studies.

"You can have a head full of amyloid and have no cognitive impairment at all, or you can have a head full of amyloid that's cleared by other drugs … and have no cognitive improvement," Miller says. "So it's now being more accepted that amyloid does not correlate to cognitive function — it's there, it's a marker for sure, and the research aimed at clearing it does what it says on the tin, but it's not meaningful in terms of how someone functions."

The focus, therefore, has been increasingly on tau, and TauRx has been there from the beginning. As of the start of 2021, there were 126 agents in 152 trials of treatments for Alzheimer's disease, according to a study from the journal Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. Of those that are considered disease-modifying therapies, 15.6% used amyloid as the primary target and 10.6% used tau.

And measuring tau has also become more commonplace in scans, as well as blood and cerebrospinal fluid assays, bringing it even further into the mainstream.

"Our focus has always been on tau, and we were considered sort of the outrider early on," Miller says. "All the conferences now are speaking more and more and more about the role of tau, about the importance of it, because it does correlate with severity of disease very clearly."

Staying optimistic

Back in 2016, TauRx suffered a blow when results from a late-stage trial of the tau aggregation inhibitor didn't meet the primary endpoint of the study, which was to demonstrate a treatment benefit in the full population.

But don't call it a failure, Miller says.

"No study fails as such because you learn something from every trial, 'success' or 'failure,' and by the very name for us, it's a trial," Miller says. "You go out to explore, does it work? Is it validated? Is it meaningful? So all trials are prone to varying degrees of success or failure."

The trials in 2016 showed researchers pivotal bits of information that the company could then build upon. In this case, Miller explains that they were using very high doses of the drug when what they needed was a reduced form with better bioavailability and penetration through the blood-brain barrier.

The other lesson TauRx learned from those trials was that their compound worked better on its own than with the standard-of-care medications the participants had continued to take into the study.

Alzheimer's disease researchers need to be a resilient bunch as victories in the area are sparse. Aduhelm was the first disease-modifying drug to gain FDA approval in 2021, and many say it comes with a hefty asterisk — trials were muddied by mixed results and regulators and payers have disagreed about its efficacy and risk-benefit ratio.

But the needle always points toward science, Miller says, and that's what drives the faith that TauRx is on the right track.

"The science is key — it can be defended, can be shown, can be supported," Miller says. "And that's what drives it so strongly and, hopefully, certainly wins out in the end."

Staying optimistic in Alzheimer's is not just important but critical for the 50 million people around the world who suffer from the disease, Miller says.

"It's one of the last great frontiers in medicine," Miller says. "It's imperative that we do something about this … so you can't help but want to keep that optimism and drive and enhance the understanding and increase the ability to do something about it."