U.S. pharma manufacturers have been wary of the generic drug market for decades. High costs, low margins and rising competition from foreign producers have transformed America’s generic landscape into a shrinking desert.

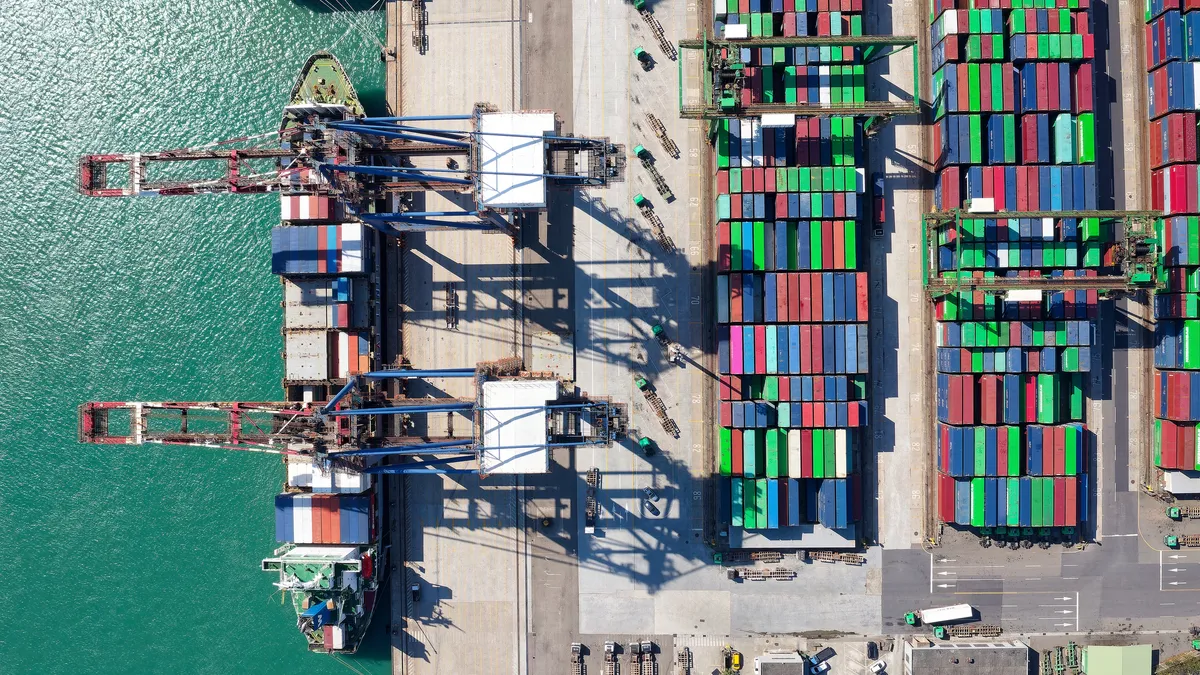

As the incoming Trump administration prepares for a new term in the White House, the president-elect has promised 60% tariffs on goods from China. While the impact would be far-reaching across industries, the drug market, which escaped the reach of tariffs enacted by Trump during his first term, is lined up for a direct hit. And because of China’s chokehold on the market for active pharmaceutical ingredients, large tariffs are likely to raise the cost of generic drugs in the U.S., which has struggled to bring more production facilities online in recent years.

“Of the 103 sites worldwide that manufacture and sell over 30 API products, just four are in the U.S., and only 15 sites in the U.S. make more than 10 API products versus nearly 350 outside the U.S.,” The API Innovation Center (APIIC), a nonprofit aimed at investing in U.S.-based drug production, wrote in a white paper published earlier this year. “In comparison, India has more than 60 API sites capable of producing 30 or more APIs and China has more than 10 such sites.”

Research suggests the problem isn’t just that the U.S. lacks capacity — it’s that the country isn’t leveraging its existing footprint. Results from a survey of nearly 40 generic drug manufacturing sites published in 2022 by Anthony Sardella, the founder and chair of APIIC, showed about half of all production capacity was going unused.

“You should tariff everything from every country forever, because if companies know it’s forever, they’ll build their factories here. Otherwise they’ll wait."

Harry Moser

President, Reshoring Initiative

“Underutilization of manufacturing capacity equates to an astonishing 30 billion doses of medicines that could be made here, by existing manufacturers in existing facilities,” APIIC wrote.

And while countries such as China, India, Taiwan and Israel have made up an increasing percentage of API production facilities during the last decade, the U.S.’s share has plummeted 61%.

With the number of blockbuster drugs coming off patent set to increase every year through 2026, there are plenty of inroads for companies looking to grab generic market share, KPMG wrote in a report.

Despite those opportunities, the market has remained “unfavorable” to API production in the U.S. and the margins remain low, said Mary Rollman, supply chain leader at KPMG.

In the years since the pandemic-era push to bolster America’s drug supply chain by reshoring production, the U.S. has yet to stake a wider claim in the global generic manufacturing market — but not from a complete lack of trying.

Signs of life

APIIC got a $14 million funding boost in September from the Biden administration to develop and produce APIs used in three common medications, drawing together the U.S. manufacturers Mallinckrodt Specialty Generics, Apertus Pharmaceuticals, MilliporeSigma and the University of Missouri–St. Louis to aid in the effort, the organization said in a release.

The cash injection follows a sprinkling of deals in the last year aimed at generic drug production.

Among the higher-profile initiatives was the 2018 launch of Civica Rx, a nonprofit consortium of hospitals and philanthropic organizations devised to tackle shortages and manufacture generic drugs. With the help of $100 million in government funding and private support, Civica built a 140,000-square-foot facility in Virginia with the capacity to produce 90 million vials of drug products — including insulin — per year.

When supply chain concerns hit a fever pitch during the pandemic, Phlow Corp. was also awarded a government contract worth up to $812 million to boost generic drug production with continuous manufacturing technology.

Phlow began operations at a facility in July that’s part of a multi-company manufacturing campus including Civica. The same month, Phlow also launched a fundraising effort for $25 million from investors.

Will tariffs bring more production back home?

Many of the larger generic drug production deals in recent years have been driven by government investments. Would tariffs open the window for more private companies to get on board as well?

Generally speaking, economists aren’t optimistic tariffs will do the trick, said Harry Moser, president of the Reshoring Initiative, a nonprofit aimed at bringing manufacturing back to the U.S.

“The whole purpose of tariffs is to overcome some of the price differences so that U.S. buyers will choose domestic products and reshore manufacturing by doing so,” Moser said. “But most economists and importers hate tariffs.”

“[Continuous manufacturing] is the kind of innovation that is going to be required to address these challenges."

Mary Rollman

Supply chain leader, KPMG

Illustrating the potential impact, Moser pointed to the steel tariffs enacted during Trump’s first term, which raised the price of some goods in the U.S. while failing to create more manufacturing jobs.

Rather than Trump’s “chaotic” tariff-based approach, Moser said he believes a value-added tax applied broadly against imports would be a more effective strategy for spurring U.S. manufacturing.

“If you’re going to do regular tariffs, you should tariff everything from every country forever, because if companies know it’s forever, they’ll build their factories here. Otherwise they’ll wait,” Moser argued. “The obvious way is a value added tax or border adjustment tax that applies to everything being imported.”

Regardless of the different strategies federal policymakers are exploring, there are signs that the appeal of reshoring is spiking. In 2012, the share of American companies that said they had recently reshored, planned to reshore or were in the process of reshoring was about 8%, Moser said. Today, the proportion has flipped, skyrocketing to as much as 90%, according to surveys across U.S. industries.

Even if tariffs create a more favorable financial environment for American producers to reshore drug manufacturing, it can take years for new facilities to come online. And according to APIIC, it will still require government investments — particularly in advanced technologies like continuous manufacturing — to bring more drug production to American soil.

Securing the future of the supply chain for generics might also look different than the traditional facility investments of the past, Rollman said. Instead, she pointed to the possibility of reshoring production to countries closer to the U.S. border. She also noted the potential impact of smaller-scale production capabilities, such as technology being developed by Continuus Pharmaceuticals, a spinout from a collaboration between Novartis and the MIT Center for Continuous Manufacturing, that could bring generic drug manufacturing closer to the “point of demand.”

“This is the kind of innovation that is going to be required to address these challenges,” Rollman said.